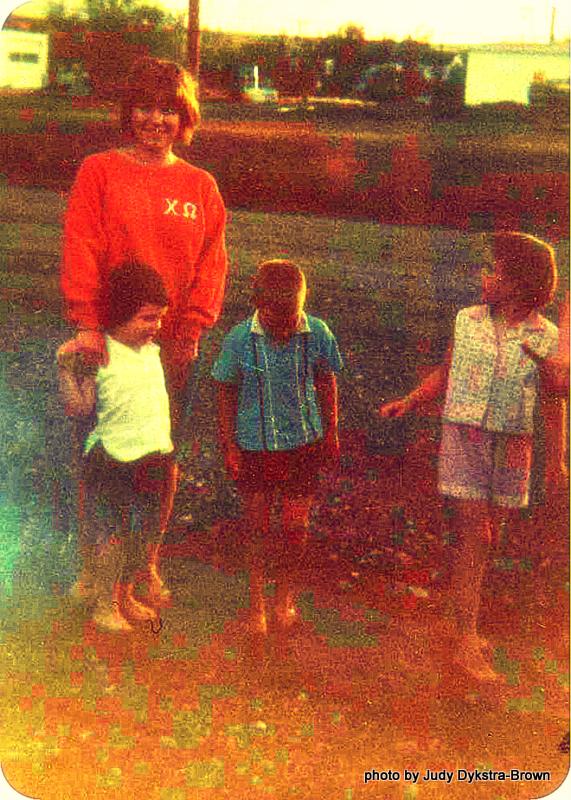

This is my sister Patti, college age, walking barefoot out to her last big adventure in the ditches of Murdo, South Dakota after a July rain. Not quite the gusher depicted in my childhood vignette below, but nonetheless, Patti’s final puddle adventure. She had taken my visiting niece out. The next day the neighborhood kids rang our doorbell and asked my mom if Patti could come back outside to play again! Ha.

Temporary Rivers

When the rains came in hot summer, wheat farmers cursed their harvest luck, for grain soaked by rain just days before cutting was not a good thing; but we children, freed from the worry of our own maintenance (not to mention taxes, next year’s seed fees and the long caravans of combines already making their slow crawl from Kansas in our direction) ran into the streets to glory in it.

We were children of the dry prairie who swam in rivers once or twice a year at church picnics or school picnics and otherwise would swing in playground swings, wedging our heels in the dry dust to push us higher. Snow was the form of precipitation we were most accustomed to––waddling as we tried to negotiate the Fox and Geese track we had shuffled into the snow bundled into two pairs of socks and rubber boots snapped tighter at the top around our thick padded snowsuits, our identities almost obscured under hoods and scarves tied bandit-like over our lower faces.

But in hot July, we streamed unfettered out into the rain. Bare-footed, bare-legged, we raised naked arms up to greet rivers pouring down like a waterfall from the sky. Rain soaked into the gravel of the small prairie town streets, down to the rich black gumbo that filtered out to be washed down the gutters and through the culverts under roads, rushing with such force that it rose back into the air in a liquid rainbow with pressure enough to wash the black from beneath our toes.

We lay under this rainbow as it arced over us, stood at its end like pots of gold ourselves, made more valuable by this precipitation that precipitated in us schemes of trumpet vine boats with soda straw and leaf sails, races and boat near-fatalities as they wedged in too-low culvert underpasses. Boats “disappeared” for minutes finally gushed out sideways on the other side of the road to rejoin the race down to its finale at that point beyond which we could not follow: Highway 16––that major two-lane route east to west and the southernmost boundary of our free-roaming playground of the entire town.

Forbidden to venture onto this one danger in our otherwise carefree lives, we imagined our boats plummeting out on the other side, arcing high in the plume of water as it dropped to the lower field below the highway. It must have been a graveyard of vine pod boats, stripped of sails or lying sideways, pinned by them, imaginary sailors crawling out of them and ascending from the barrow pits along the road to venture back to us through the dangers of the wheels of trucks and cars. Hiding out in mid-track and on the yellow lines, running with great bursts of speed before the next car came, our imaginary heroes made their ways back to our minds where tomorrow they would play cowboys or supermen or bandits or thieves.

But we were also our own heroes. Thick black South Dakota gumbo squished between our toes as we waded down ditches in water that flowed mid-calf. Kicking and wiggling, splashing, we craved more immersion in this all-too-rare miracle of summer rain. We sat down, working our way down ditch rivers on our bottoms, our progress unimpeded by rocks. We lived on the stoneless western side of the Missouri River, sixty miles away. The glacier somehow having been contained to the eastern side of the river, the western side of the state was relatively free of stones–which made for excellent farm land, easy on the plow.

Gravel, however, was a dear commodity. Fortunes had been made when veins of it were found–a crop more valuable than wheat or corn or oats or alfalfa. The college educations of my sisters and me we were probably paid for by the discovery of a vast supply of it on my father’s land and the fact that its discovery coincided with the decision to build first Highway 16 and then Interstate 90. Trucks of that gravel were hauled to build first the old road and then the new Interstate that, built further south of town, would remove some of the dangers of Highway 16, which would be transformed into just a local road–the only paved one in town except for the much older former highway that had cut through the town three blocks to the north.

So it was that future generations of children, perhaps, could follow their dreams to their end. Find their shattered boats. Carry their shipwrecked heroes back home with them. Which perhaps led to less hardy heroes with fewer tests or children who divided themselves from rain, sitting on couches watching television as the rain merely rivered their windows and puddled under the cracks of front doors, trying to get to them and failing.

But in those years before television and interstates and all the things that would have kept us from rain and adventures fueled only by our our imaginations, oh, the richness of gumbo between our toes and the fast rushing wet adventure of rain!

This is a rewrite of a story from three years ago. The prompt today was ascend.

Beautiful memories. So different too from the city kid from New York. But we both wound up where we wanted to be 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. What did you do when it rained in New York?

LikeLike

Pretty much the same thing, actually, although we had somewhat more paving than you. But — we lived in a rural “corner” of Queens. My house stood on almost 3 acres of woods — oak mostly. When my father was here, briefly, maybe 12 years ago, he looked out our front window and said: “This reminds me of Holliswood. Remember? Looking out our picture window and all we could see were trees?”

Until he said that, I hadn’t realized how much this place reminds me of where I grew up. Not the house, which is utterly different, but the place. Yet we were just 1/2 mile’s walk to the subways into the city. Technically, Holliswood WAS the city. The people behind me raised chickens and had an acre of corn. Down the block, they raised donkeys and had flocks of geese that roamed the street. if my family hadn’t be psycho nuts, it would have been an ideal childhood. Pity how people can ruin a good thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for that, but glad for how well you turned your life around.

LikeLike

You know — you, me, Martha, Pat Gerber, Tish Farrell and a few others we circle around with — we’ all few up in a different world than the one in which we now live. All of us have traveled, too. Together have an amazing book of women who have lived lives that were unexpected and possibly interesting. Just a thought.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You put it together and I’ll contribute. Might be interesting to have stories from different stages of life. We probably all have them on our blogs. I am so loathe to quit blogging long enough to get a book together that instead I am checking when I get my daily prompt and if I already have a piece making use of that word, I rewrite it instead and repost (if it is at least 3 years old, sometimes 2) When I read them they seem new to me so I imagine bloggers are either new enough to my blog that they haven’t read them or that they’ve forgotten them as I have. Ha. At any rate, it affords me the opportunity to look at old work and edit rather than continuing to push out new work.

LikeLike

Lovely.

LikeLike

Oh my I LOVE this!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some of my best memories were rain-inspired. Not a very frequent happening in Dakota.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love rain and did not realise Dakota was that dry, I so enjoyed that post.

LikeLike