Innocents in Mexico

Chapter 17

For the next two days, there were almost gale force winds followed by torrential rains. Pots in the compound blew over, their tall plants having been blown like sails by the wind. The streamers which hung across the road came detached at one end and tangled around the telephone wires. We had invited our first guests over for dinner on the first day of strong winds. As the hour approached for their coming, I kept hoping that the winds would stop. Our dining room table and chairs were on the roofed but unwalled patio off the kitchen. I put out candles, but they blew out. Any time I moved out to clean or rearrange chairs, the heavy glass and metal door was caught by the wind and slammed shut. By five o’clock, Bob had agreed that the weather was not going to cooperate and we moved the furniture to the sides of the living room and moved the table and chairs into its center. I collected bougainvillea from the lush plants in the patio, a few branches of each color. I arranged them around the hors de ouvres and made bundles of forks, spoons and knives which I wrapped in napkins and tied with waxed linen, slipping a sprig of bougainvillea in each one. The day before, I had disinfected the fruit and vegetables, made the spaghetti sauce. That day, we had shopped for bread, driven out to the hacienda to check on the progress of the remodel of the house Ernesto wanted us to rent. We had checked out other areas as well. I still didn’t feel like it was my place. It was too cut off.

Ernesto was slated to arrive at our house at 7 p.m. Dirk, who had to pick up Maria at work, thought they’d be there by 7 p.m. At 6:55, Bob said, “You know, in one of our books about Mexico, it says that Mexicans are too polite to turn down your invitations to dinner, but that sometimes they just don’t show up.”

“It’s not even seven,” I told him. “Besides, Ernesto wouldn’t do that. And Dirk’s American––he wouldn’t either.”

Ernesto was almost on the dot, walking in the door with a bottle of tequila. “I want you to taste this, “ he said. I poured a shot glass full. “No, no. You have to drink it with a little grapefruit juice or orange juice. “

I poured mango juice on top of the tequila and drank it like a shot.

“See what it says on the label?” said Ernesto, “By appointment to the king. It just doesn’t say which king. Do you know how much it costs?

At the present rate, it was about $2 per bottle.

“If you want it to taste smooth, put a slice of potato in it and let it set. Then remove the potato and the tequila will be smooth.”

Dirk and Maria arrived a half hour or so later, Dirk hurried and flustered and apologizing. He had driven down our street before going to get Maria so he’d know where to go, but he couldn’t find the house. Either I’d not given him the address or he’d forgotten to write it down. He brought a bottle of red wine, but I gave him a rum and coke to tame him down.

“Is this it––are we the only guests?” he asked, surprised.

“You’re it. And we expected you to be late. We know about Mexican time.”

Dirk was aghast. They didn’t operate that way. Maria Antoinette was calm as usual. She had simply insisted they stop each person they saw on the road and ask where the foreigners were. They kept pointing them onward and saying, “Jim, Senor Jim,” which was the name of our landlord. Eventually, they’d found it. We’d taped a small note to the door and left the gate ajar.

The party was loose and fun. Dirk admitted that it was the first time they’d been invited out to dinner in someone’s home the entire time they’d lived there. They’d been invited to one fiesta with many people, but not to a private home. He seemed thrilled. Ernesto was warm and charming. He told us some of his stories over again. Everyone ate heartily, commenting on the food and taking seconds. “Do you have any more of those long vegetables?” asked Ernesto, and I went to the side table to get the asparagus.

Wine, tequila, rum and Corona were paid proper attention to by Ernesto, Dirk and me. Bob drank Coke light and Maria drank fruit juice. After dessert, Ernesto brought out his guitar and played trickily fingered Mexican and Spanish love ballads. “I took the crystal glass and broke it. With the shard, I opened my vein. I thought of my loved one, now vanished. I will never love again.” He mouthed the words in English as he strummed and picked, first slow, then fast in the Latin manner. Then he sang them in Spanish.

All of the songs were love songs––lush and full and romantic. Earlier, he’d mentioned his girlfriend and, horrified, I said that he should have brought her. I didn’t think to ask if he had someone he wanted to bring. “No, on Tuesday night it is her night to go out with friends,” he answered. “So I just didn’t tell her. She’s not beautiful or anything,” he explained.

We didn’t know what to make of this comment from Ernesto, who was always courteous and polite. He said it as though it was just another fact, but it revealed the other side of the coin from the romantic music––the practicality of having a girlfriend, even though she wasn’t beautiful as opposed to the second song he sang, “Into each life, there comes one love. Now that she’s left, I’ll never love again.”

Dirk told lots of jokes about breasts. I told them about Bob greeting strangers on the street with “Buenos nachos.” Ernesto laughed especially long, then told us that if he ever had said “Buenos nachas,” he was telling them that they had nice butts. I told them about the time in Minneapolis in the July heat when we had been leaving a restaurant. Bob had on shorts and as he walked out, a woman in her sixties was coming in. “Nice legs,” she commented to Bob as he held the door for her. Her husband, horrified, said, “Why would you say such a thing?”

“Because he has nice legs. He does,” she said, standing her ground.

She was right, he did have the nicely muscled legs of a bicycle racer which lived on long after his bicycle racing days were over.

When they left at 11:30, Dirk again mentioned that this was a highlight in their life in Mexico. “I’m going to e-mail Richard and tell him all about it,” he said. He told Richard, an old friend and fellow dentist, everything. Richard had been the link between Ernesto and Dirk, having corresponded via e-mail with Ernesto for a year. Although they’d never met, they felt like old friends. Then Richard had sent a picture of Dirk and said he and Ernesto should meet. The second day when I’d met Ernesto in the library, he’d been slated to meet Dirk a half hour later. I’d stayed on and so witnessed their meeting. Richard, they told me, had a half million dollars he wanted to invest in Mexico. When he came, they would throw a huge fiesta and we would come.

“Do you know enough people to throw a huge fiesta?” I asked Ernesto.

He laughed, “If you throw a fiesta, the people will come.”

For Chapter 18, go HERE.

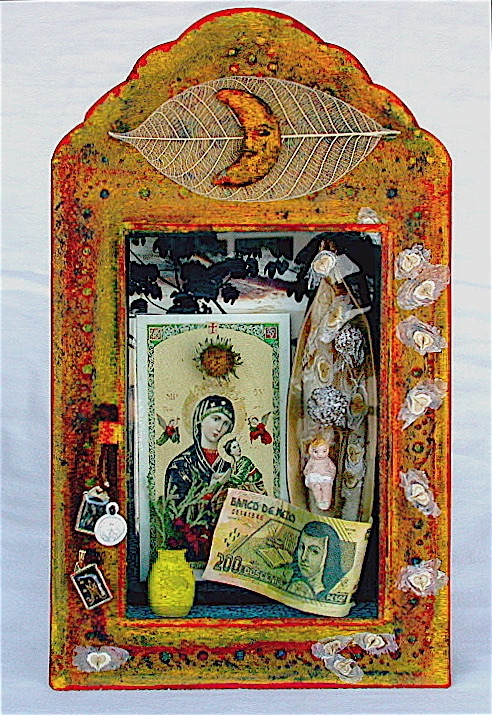

Although I can’t find any of the photos I took in San Miguel, the background of this retablo I made while living there shows a shot of the courtyard of the hacienda where Ernesto wanted us to live.

Although I can’t find any of the photos I took in San Miguel, the background of this retablo I made while living there shows a shot of the courtyard of the hacienda where Ernesto wanted us to live.

Bob, 2001

Bob, 2001