Find Chapter 1 HERE Chapter 2 HERE Chapter 3 HERE Chapter 4 HERE Chapter 5 HERE Chapter 6 HERE

Innocents in Mexico

Chapter 7: Posada de las Monjas

It was Sunday, May 13, at 1:30 a.m. It was our first night in our new room, and someone was setting off fireworks. They soared up into the air and exploded with ear-splitting booms. Dogs barked from half the rooftops of San Miguel. There were too many lights in town, even at this late hour, for the stars to be visible. It was a shame as our room was so high that we had a panoramic view of the city and the sky. Below us, tin roofs broke the spell, but we had occasional glimpses into courtyards full of plants and trees. A cat yowled below and Bearcat stood and stretched but did not scoot under the bed as he had that afternoon when he heard the same caterwauling. He was getting braver every day, but a car backfiring a block away or a door slamming across the courtyard could still send him into hiding. We had no yard now for our midnight walks. All of the courtyards and terraces in this hotel were of cobblestone or cement. He was an illegal alien here. When we sneaked him out on his leash at night for a walk through the deserted outside corridors, he was calmer, walking as close to the curtained windows of each room as though eavesdropping for any possible news of his new environs. Although the management didn’t know we had a cat, some of the staff knew but they never told. This first night, we settled to bed, finally, by 2 a.m. and I penned this poem a mere four and a half hours later:

San Miguel Morning

The sounds of rooting cats

like infanticide

accompany

tuba music

in 4/4 time.

Fireworks.

Roosters.

Donkey brays.

6:29 in the morning.

All’s right with the world.

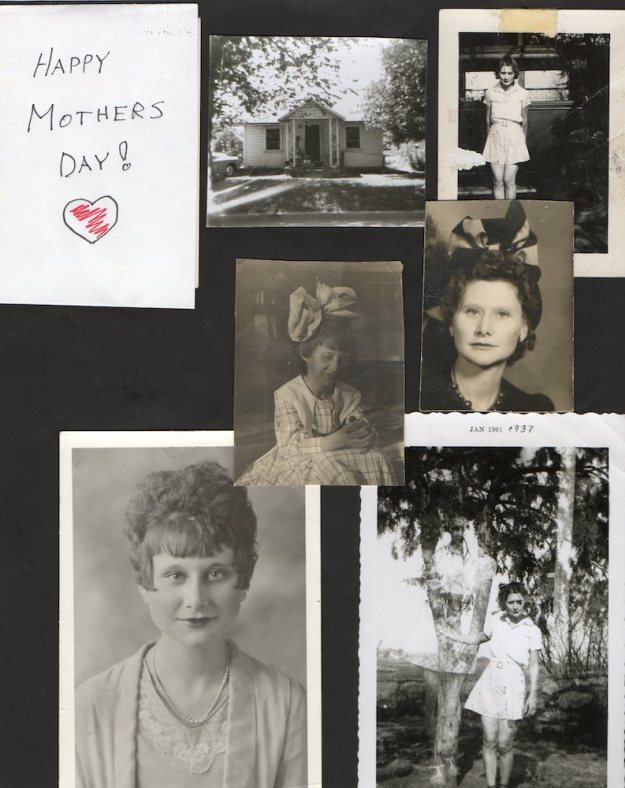

Today was Mother’s Day. It was the first in my life where I had no mother to send flowers to. The same was true of Bob. On our way through Tucson, we had stopped to see my mother’s crypt for the first time. I had meant to bring flowers, but I could see that they didn’t allow fresh flowers, and I couldn’t bring myself to leave plastic ones. Some of the crypts had metal flowers attached, and I decided to try to have something special made in Mexico. Those would be the flowers I sent this year.

On this day, we took the van out of the courtyard of the hotel to go look at an apartment. It was a bother to do so, because it meant getting a man to open the portal––not only the one that could be reached from ground level, but also the high one 8 or more feet off the ground. Today, the guard used a tall metal pipe to pry the hatches open, Yesterday he had attempted to climb up on the lower lock to reach the top one, but it was a tricky maneuver and he had fallen off.. Then we scraped the bumper of a new yellow pickup trying to back out.

The apartment we saw was a depressing empty house in an extremely poor neighborhood. On the floor of the bare living room was a pair of men’s slacks, rumpled as though he had climbed out of them and left them as they were. Half-full bags of grout lay abandoned. In the shed, there was the overpowering smell of oil paints. What had been described as a garden was hard baked earth with a few abandoned flower pots. Even the weeds were dried and skeletal. The house described as furnished in the newspaper ad was dark, in poor repair and completely empty. The woman told us she had no money to buy furnishings, but maybe they could get one bed and a refrigerator.

That afternoon, we had been looking at pictures of rentals in a rental office near our hotel. The apartments and houses were all picture perfect––decorated, furnished with art and gardens complete with gardeners. The contrast was so depressing that it made me again question whether I wanted to stay here.

The disparity between the gringo sections of town and the local sections was so great. And yet in the restaurants and galleries, I saw the majority of people were Mexican––well-groomed and prosperous looking––eating the same food and drinking the same drinks we were drinking. Our hotel, too, was filled with Mexican travelers, so the difference was not so much one of nationality as of level of prosperity. The same economic differences existed in the United States, but there, as here, we were shielded by the distances between our living areas.

Even in the U.S, there were places we never went. Why would we? In those places there were no restaurants, theaters, gyms. In those places, there were none of our friends to visit. Our kids didn’t go to school in those neighborhoods, so for us, they didn’t exist. Every American we talked to said not to have a car here––to depend on public transport or walking, but public transport did not take them through these neighborhoods, so for most, I am sure they did not exist.

By the time we got home again, we were exhausted from trying to negotiate the maze of unmarked streets. To compound our frustration, we found that the lot that had been nearly empty when we left was now completely packed––with all cars double parked. The guard fit us diagonally into one corner of the large courtyard in a place where we blocked four cars instead of two. He refused to take our car keys, so we imagined an early knock on our door to get us to come move it. We had already made the decision to keep the van in the compound for the rest of our stay, but this cinched it! On Monday, we would take a taxi to immigration and the real estate office. Already, our new van had rattles in every part of its chassis from two days of bumping over cobblestones. The side was scraped and the running board dented in. If we had to count the number of streets backed down or tight spaces we had turned around in, it would reconfirm our decision. A car in this town was crazy. A full-sized van was lunatic. People drove vans the size of ours as buses here.

It was a moral struggle to sit in the Plaza Principal. Every time I sat down, an old woman came to sit next to me to tell me she was hungry. When I told her I didn’t understand, she sighed. She sat for fifteen minutes, sighing every few minutes or so. Finally, she asked me the time. At first, I didn’t understand. I thought she was pointing out the dark freckles on my arms. Then I understood the word “Hora.”

“Seis?” she asked.

“Siete,” I answered. I knew some Spanish. Now she would suspect I really understood her. Well, I guess I did, even without words. On our first day, Bob and I gave money out to most who asked. When the same people approached us later on their next round, we realized that it was endless. To encourage the woman and children selling cloth dolls meant no time ever in the jardin when we would be free to read a book or watch the strollers or the church facade changing colors as the sun moved across its face. It meant constant interruptions to the peace and tranquility we had come here to find.

It was a major conflict that all of us face in this world. Were we here to enjoy the world or to confront and deal with its miseries? Was it fair to choose the ways in which we tried to make the world a better place? Was it making the world a better place to encourage begging? Was there any alternative to begging for those who did so? I remembered the old woman who fell down in a faint in front of the church in Oaxaca. Kind tourists helped her into a sitting position, fanned her, pressed coins upon her. Then one of the locals laughed and told us that she was one of the richest women in town––so good at her daily act that she made more than most wage earners.

I remember the children in Bombay whose parents had cut off their arms or legs to make them more successful at their begging. Where were the easy answers? There were none. If we taught at the free art school, would it make a difference? It would make a difference for us, ease our guilt. But would it do enough to ease the suffering in the world? The answer was clear. We would do what we could do: try to be kinder, try to notice instead of reacting the same to every person who asked for our help. We would live here not quite adequately, as we had lived in every place. We were not Mother Teresa, nor were we Hitler. We were fugitive Americans trying to find a better way. We were trying. Looking. Tomorrow we would see what happened.

Again, the old woman sat by me in the Plaza Principal. I was no longer sure that she remembered me as the same person every time she sat down. This time she asked me if I lived here and when I said no, she asked me where I lived.

“El Norte,” I told her. Bob and I were sitting on extreme ends of the same bench because each end had a tree which sheltered us from the brief afternoon rain. She crowded with me under my arboreal umbrella.

“You have beautiful hair,” she told me, which I did not understand until she pulled at her own hair and said, “Amarillo. Bella.”

When I pulled out a bottle of water. “Ah, Agua” she sighed, and pulled out a plastic bottle of Pepsi from her string bag to take a drink.

“Ese es su esposo?” she asked, pointing at Bob.

“Si.”

For the next ten minutes or so, she sighed, now and then, asking me for money for food under her breath, but I could feel that her enthusiasm had waned. Occasionally, she commented on those who passed us.

“Buenos tardes, senora,” I said, when we got up to leave, but she was already moving to another bench.

For Chapter 8, go HERE.

For Cee’s FOTD

For Cee’s FOTD