The youngest member of our family (Maddie, 9 months) seems rapt over the words and motions of our eldest, (Jane, 90), or perhaps she is just admiring her beautiful manicure.

The youngest member of our family (Maddie, 9 months) seems rapt over the words and motions of our eldest, (Jane, 90), or perhaps she is just admiring her beautiful manicure.

Category Archives: Family

Gathering Family

Tonight marked the end of our two day family reunion with my mother’s side of the family. The matriarch is Jane, 90 years old, and the youngest was Maddie the miracle baby, age 9 months. I am somewhere in the middle, but closer to Jane by one year as of midnight. I unfortunately don’t see these lovely people often enough, but every time I am around them I’m appreciative of their closeness and acceptance of either others’ differences.

I had a wonderful time, as you might be able to gather from these photos. (You might want to click on them to enlarge them.) The statue of Lincoln marks the highest point on the Lincoln Highway. We passed it this morning as we drove from Cheyenne, Wyoming to Laramie to visit Jane in her daughter Sara’s house. In college, the art class I was in came up on a cold blustery day to scrub him down with acid. Yesterday, we just stopped to admire him in his new spot next to the new wider interstate road. He’s been raised up a good deal on a very high pedestal, so I wouldn’t relish giving him a scrub now.

The other photos were taken in three different locations as different events were held in three different homes. Representing my mother’s branch of the family were my niece Cindy, my sister Patti and I. All of the rest were descendants of my mother’s sister Peggy and their spouses. Lots of laughter, fun, memories, discoveries and great food.

Jubilant

I knew immediately which photo I would use when I saw this week’s word prompt. This picture was taken of my sister Patti greeting my husband Bob at my nephew Jeff’s wedding. It was taken long before digital cameras were invented. Thanks, technology, for good scanners to translate all these old photos as well as simple editing tools to remove the specks they all seem to contain. I know the quality is terrible, but I could not resist using it.

And since there is no such thing as too much jubilation, here are some more:

(Click on first photo to enlarge all photos.)

Locked and unlocked

Locks

Locked up in my bedchamber. More than I can bear.

The beauty of my countenance, the shimmer of my hair

do me no good for no prince charming comes to find me here.

I will go unmarried––for my whole life, I fear.

My father thinks he honors me. I am his special treasure.

He worries not about my fate. He thinks not of my pleasure.

I am but one more lovely thing he keeps for his collection––

admired for my golden locks, my flawless pale complexion.

I care not for beauty. I care not for my tresses.

I do not treasure jewels or slippers or my ornate dresses.

A husband and a family are all that I desire.

A simple life’s the sort of life that I most admire.

From my window I look out upon the broad King’s Highway.

All roads must converge here––every path and byway.

And so I see them passing: beggars, countrymen and princes.

Vendors selling mangos, apples, oranges and quinces.

My eye is caught by sunlight flashing from his sword

as he stoops to have a sip from a vendor’s gourd.

He pays her with a small coin and thanks her most politely,

then mounts his horse with one sure leap–graceful, sure and spritely

I see him passing often and his face is full of laughter,

calling out and gesturing to companions, fore and after.

One day I wave my scarf at him as he goes passing by

and every day thereafter, I know I’ve won his eye.

At first he bows politely–a gesture I don’t miss.

and after a few weeks of this, one day he blows a kiss.

I reach out and grab it and press it to my face.

He rears his horse and races off at a faster pace.

The next day he doesn’t come, although I wait and wait.

But finally, I see him turning towards my father’s gate.

In distress, I call out that he must not tarry here.

My father’s wrath must not be stirred. It is what I most fear.

He does not see me gesturing. He hears not my distress.

I rue the day I waved at him, although I must confess

I also thrilled to think that he had come in search of me.

I fantasized that he would be the one to set me free.

But my prince never entered, though he tarried long and late.

Until the full moon rose above, he waited at the gate.

Although it had not opened by the time the next sun rose,

the young man sat astride his horse with hoarfrost on his clothes.

‘Twas then that I began my moan and tears sprang from my eyes.

I tore my clothes, scratched at my face. I’d ruin my father’s prize!

My serving maids, sorely distressed, tried to stay my hand,

while my genteel companion sat with startled eyes and fanned!

When one maid put down the apple she’d begun to pare,

I grabbed the knife and severed one long lock of hair.

Lock after lock, I parted with this prison I had grown.

I’d see if father still wanted a daughter newly mown.

Then outside my chamber, I heard a deafening grate.

I flew back to the window. They were opening the gate!

At the same time, I heard a knock and my door opened wide.

I knew it was my father in the passageway outside.

I feared his consternation, his anger and his wrath,

and yet I chose to put myself squarely in his path.

In one hand I held half my locks, in the other were locks more.

All my other shorn-off glory, around me on the floor.

“I am not your possession,” I tell my father then.

I am no pretty pet that you can lock up in a pen.

You can have my beauty––” (Here I handed him my locks.)

“but you cannot seal me up in your private box.”

My father raised his hand, and I feared that he would strike me––

angered that he’d never again have a treasure like me––

but instead he circled his arm around my shoulder

and said, “This day, I have acquired a daughter who is bolder!

It was never me who kept you sealed up in this tower.

You always had it within you to unlock your own power.

You must know this unlocking is both metaphor and literal.

The freedom that you’ve won today, both actual and clitoral.”

And that is how this princess, once set upon a shelf,

learned that the price of freedom is to win it for one’s self.

By cutting off my own locks, I opened up the gate.

My reward––the clever prince wise enough to wait!

Helen Meikle sent along this song which she said had a similar theme to my poem. Can’t believe I’ve never heard it before…but I agree. Listen to it HERE

Legacy

Legacy

The thoughts and looks and talents of others of my kind

are written on my body and written on my mind.

My genetic family, departed from this earth,

exists in my coloring, expression, voice and girth.

I’m glad I got mom’s optimism and her rhyming wit,

but her success with pastry? I have none of it.

I cannot bake a cherry pie. Light pastry is a riddle.

The few cakes that I ever baked were soggy in the middle.

Why couldn’t I inherit my mother’s slender legs

instead of my Dutch aunties’ solid ample pegs?

For women on my dad’s side were noted for their girth

as well as for the many years they spent upon this earth.

Thin skin that picks up bruises from each ungentle touch?

I’ve inherited it all–thank you very much!

My mother’s taste for chocolate, my uncle’s taste for gin––

both sides of my family I carry safe within.

My grandmother’s hands that always needed to be busy,

my Aunt Stella’s tendency to wind up in a tizzy.

“Blahsy blah!” she would exclaim, and flop her arms and walk

in tight little circles. I couldn’t help but gawk.

But sometimes I find myself getting flustered, too,

my mind stomping in circles as I figure what to do.

My upper arms look more like hers, my stomach like my mother’s,

although I’d rather have Aunt Betty’s if I had my druthers.

I could go on for stanzas, listing each thing that I’d rather,

but my recital has already turned into mere blather.

So I’ll just say a thank you to those who came before.

For in spite of all your ills, I have you at my core.

Somehow the parts you left in me, although they aren’t all pretty,

are very rarely mean or dumb or dense or dull or petty.

You left me curiosity that fills out all my days––

as well as that Dutch work ethic that doesn’t let me laze.

Dad and Mom, I thank you both for your good sense of humor

and for your facility at blending fact and rumor

into stories that you then simply had to tell.

And thank you for instilling the need to tell them well.

Slight exaggerations are expected, I have learned––

one vital ingredient of stories finely turned.

And though each story must be told starting at its top,

the secret lies in simply––knowing when to stop.

If you haven’t had enough, HERE is another piece I wrote to a similar prompt.

https://dailypost.wordpress.com/prompts/legacy/

WordPress Weekly Photo Prompt: Harmony

Harmony

(Cliick on first photo to enlarge, then arrows to proceed through photos.)

What Vestige Left?

What Vestige Left?

I think what any of my ancestors would find most surprising if they were to come back is that there is so little of them left. My paternal grandma would look for her quilts, her embroidery and her China cabinet full of glass and porcelain and would find none of them in my house. I spent too many years traveling, so my older sister Betty Jo and my cousin Betty Jane wound up with all of grandma’s things. The one good quilt is over Betty Jo’s bed in the managed care facility where she now lives, but she knows nothing of it or of us or of her own children, being the prisoner of Alzheimer’s that she is.

My cousin Betty Jane passed on years ago, so the China cabinet full of Grandma’s dishes is in Idaho in the house of her second husband. What Grandma would find of herself in my house is:

one blue bowl filled with jade plant cuttings by my kitchen sink,

an old pottery canning jar above my kitchen cabinets––

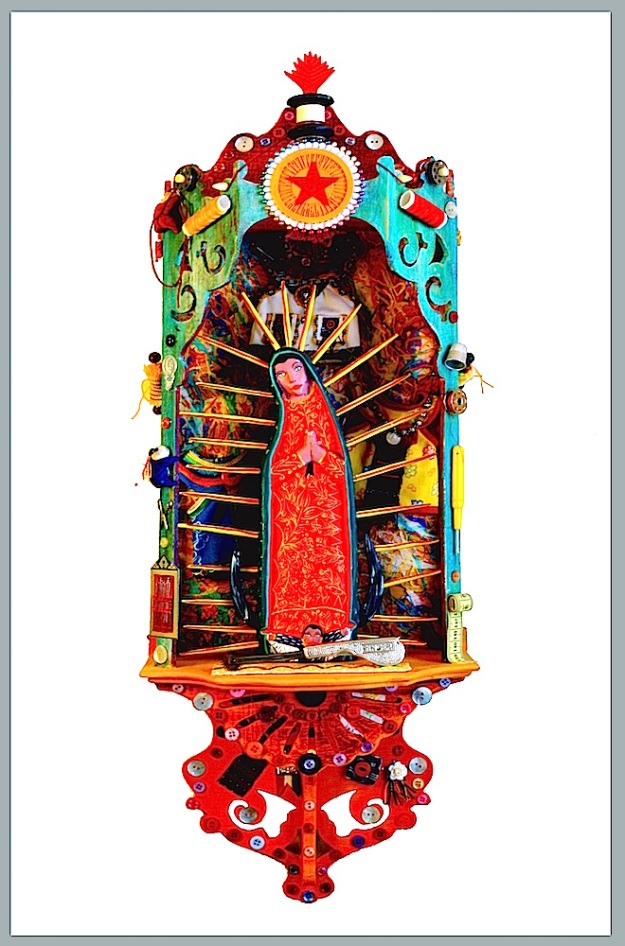

and remnants of her tatting, a small square cut from a pillowslip she embroidered and part of a quilt square that I used in a retablo entitled “Our Lady of Notions.” (The view above is looking down on the top of the retablo–details not shown because of the shooting angle in the view of the entire retablo below.)

Amazing that so little remains of her in my house when she had a house stuffed full of things. Now that I am the one with the house stuffed full, I wonder what of me will remain after fifty years. Perhaps just this blog or my books or my artwork. Maybe that is why I am so compulsive about writing and doing art–that need to be remembered.

Amazing that so little remains of her in my house when she had a house stuffed full of things. Now that I am the one with the house stuffed full, I wonder what of me will remain after fifty years. Perhaps just this blog or my books or my artwork. Maybe that is why I am so compulsive about writing and doing art–that need to be remembered.

The Prompt: Modern Families––If one of your late ancestors were to come back from the dead and join you for dinner, what things about your family would this person find the most shocking?

https://dailypost.wordpress.com/prompts/modern-families/

Freudian Slip

Freudian Slip

Caught in the tangles of last year’s castoff wreaths in our local cemetery, I found the following words. They were scrawled in a frenzied adult handwriting in fading purple ink on a curled yellowing slip of lined paper with one jagged edge, as though it had been ripped from a journal:

Behind the door of my dream, I heard a knocking. I walked down a tree-lined corridor to the door at the end. As I drew nearer, the knocking grew louder and more frenzied. I struggled with the bolt, which would not open, but as I finally drew it back, there was an explosion of sound—organ music playing a dirge in such a joyful manner that it sounded like a celebration instead of the reflection of death.

As the door creaked open, I heard the crash of glass breaking and then the tinkle and scrape of this glass being ground down to shards and powder as the door opened over it. There was such a bright light shining from behind the figure standing on the other side of the door that I could make out only her silhouette—a woman with an elderly stance wearing a long skirt. She was large of bosom and had thin wisps of hair piled untidily on top of her head. In one hand, held down to her side, was a basket. In the other hand was a jar.

I drew closer to the woman, to try to get her body between my eyes and the source of the bright glare—to try to see who she was. When I was but six inches from her, I finally recognized her as my grandmother. She was wearing the same navy dress with pearl buttons and gravy stains down the front that she had been wearing the last time I remember seeing her. In the basket was a mother cat with three kittens nursing. In the jar was chokecherry jelly, if its handwritten label was to be believed.

As I drew up to hug her and kiss her cheek, she started humming a song—some church hymn, perhaps “Jesus Loves the Little Children.” It was hard to recognize because she hummed it under her breath—with little inward gasps at times that made it sound like she was eating the song and then regurgitating it.

Her eyes were vacant as she looked over my shoulder. “Grandma, it’s me!” I said, but she still didn’t look at or acknowledge me.

“Do you want to play Chinese Checkers?” I asked. It was the one activity I could remember that both my grandma and I enjoyed.

She expressed a long intake of breath, shook her head no and held out the basket to me.

“Is this a gift?” I asked.

“No, it is an obligation,” she hissed, and as the basket passed from her hand to mine, she seemed to deflate—whooshing backwards out of sight—until only the basket of cat and kittens and the jar of chokecherry jelly lying sideways on the trail she had vanished down gave testimony to her presence.

“Bye, Grandma,” I called wistfully down the trail she had vanished down. “I love you.”

But I didn’t love her. I had this memory of sleeping with her in her feather bed and almost smothering trapped between the thick feather pillow and comforter. I have an explicit memory of holding the pillow over her face and her struggling to get free. It was a joke and I hadn’t meant to smother her, really, but there was such power in the fact that she could not fight off an 8-year-old girl that it made me hold the pillow over her face for a few seconds longer than I wanted to or should have. She was all right. Just frightened as I had been frightened so often by her stories of poor little Ella and all the wrongs done to her in her lifetime. It was as though I had to choose sides—her side or the side of the people who had done mean things to her. And like the little devil she always made me out to be—I chose the other side.

The Prompt: Everything Changes––You encounter a folded slip of paper. You pick it up and read it and immediately, your life has changed. Describe this experience.https://dailypost.wordpress.com/prompts/everything-changes/

In response to The Daily Post’s writing prompt: “Life’s a Candy Store.” You are a 6 year old again How would you plan a perfect day?

My dad and I at the Deer Huts when I was about 3.

My dad and I at the Deer Huts when I was about 3.

Black Hills Reverie

My dad is coming with us–he doesn’t have to work.

Corn muffins in the oven, and coffee on the perk.

It’s orange juice for sis and me. I take a little sip.

We woke up really early to start out on a trip.

We’re going to the Black Hills where we will spend the night.

We’ll start out just as soon as we have had a little bite.

We’ll stop to pick up my best friend who will go along

They’ve let me plan the whole long day, so nothing will go wrong.

En route we’ll stop at Wall Drug and have an ice cream cone,

then drive on through the Badlands, as dry as any bone.

My dad will sing a song for us–“Lonesome Mountain Bill”–

and let up on the gas petal as we crest the hill

to give our stomachs all a lurch and a little flutter.

My mom will say “Oh Ben!” and then my older sis will mutter.

But Rita and I love this trick and we will urge another–

an action nixed first by my sis and then by my mother.

We’ll stop at Petrified Gardens and see the fossils there,

buy rose quartz and mica and other rock chips rare.

Then on to Reptile Gardens where they wrestle crocodiles,

to ride on giant turtles and view other reptiles.

We stop next at the Cosmos where gravity’s gone amuck.

We’re doing everything I wish. I can’t believe my luck!

On to old Rockerville Ghost town where we have our dinner.

If I resisted cherry pie I know I would be thinner,

but with a scoop of ice cream it really is delicious.

Just try to keep it from me–I’m likely to turn vicious!

Next we drive the pigtails, where the road just curls and curls

passing over and over and thrilling three small girls.

We’re going to see Mt. Rushmore–those giant perfect faces.

Perhaps we’ll buy a souvenir if we’re in Dad’s good graces.

Then on to drive Custer State park with the begging burros.

We’ve saved some treats from Rushmore–some peanuts and some churros.

Back to Rockerville we go for supper and a show.

The “Mellerdrammer” (sic) is the place where we’re going to go

to hiss the villain from the crowd, throw peanuts at his back

as he ties the heroine to the railroad track.

Then drive the seven miles to my favorite sleeping place,

though mother doesn’t like it, and she makes a funny face.

“The Deer Huts” are just cabins right up in the trees

and we have to use the outhouse to take our bedtime pees.

We get to walk with flashlights and pick our way with care,

through the ponderosas, where perchance we’ll meet a bear!

I love the moonlit shadows and the night bird calls,

being extra careful to avoid stumbles and falls.

Sometimes we fake the need to pee to take another walk,

and on the way my friend and I walk slowly as we talk

of all the things my parents have let us do today.

We both agree that this has been a perfect sort of day.

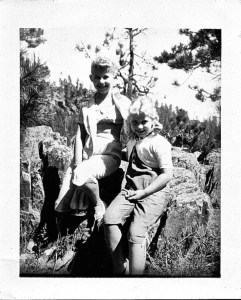

My sister Patti and I in the Black Hills, age 7 and 11.

My sister Patti and I in the Black Hills, age 7 and 11.

In South Dakota, lunch was dinner and dinner was supper. For the sake of authenticity, I’ve maintained the custom in this description of a child’s perfect day.

Generational Drift

Generational Drift

My mother would have been the first one to say that she was lazy. To be fair, this wasn’t true. I had seen her iron 32 white blouses at a sitting—her at our large mangle, running the fronts and the back of the garments, then the sleeves and collars through the large rollers, my sisters or I then taking our turns ironing the details near the seams and around the buttons. We had a regular assembly (or wrinkle de-assembly) line going every Saturday morning.

She cooked every meal and kept the house reasonably clean. But on weekends, she was the commander and we were the workers. One vacuumed while the others dusted. We were the window cleaners and the front walk sweepers, the table setters and dish washers when school or social activities allowed.

But there were times when a good book consumed each of our interests to a degree that weekend chores were lost in a blur of fantasy–each of us in thrall to a different book–my sisters in their rooms or on beach towels spread out in the sun of the back yard, me on on my back on the porch roof just outside my older sister’s bedroom window, and my mom flat on her back on the living room sofa.

Or sometimes it was the same book–taking turns reading 9-year-old Daisy Ashford’s memoir “The Young Visiter” [sic] as the rest of us howled–holding sore stomachs, tears running down cheeks. At times like this, a week’s clutter might sit untouched on surfaces, that morning’s dishes still in the sink, last night’s shoes still lying like rubble in front of the t.v. or half obscured beneath piano bench or assorted chairs around the room.

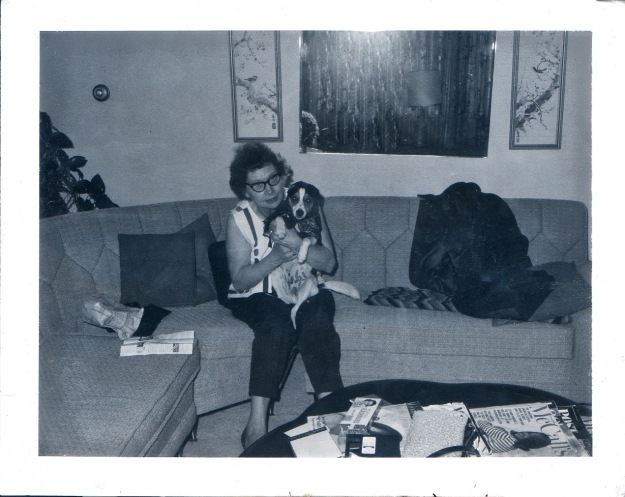

In short, housework, although generally done weekly, never got in the way of activities or a good book. We were a family of readers, and generally this reading was done on our backs. My mother’s spot was always the living room couch–some family pet (a tiny rabbit or raccoon, kitten, or the family terrier, Scamp) spread out between her side and the divan, my dad in “his” comfy rocking chair, feet up on the foot stool. I loved my bed or the floor or in the summer, outside under a tree. My older sisters’ bedrooms were sacrosanct. A closed door meant privacy. No one entered uninvited.

This was in an age before computers, cellphones, or other texting methods. The one telephone in our house was on the kitchen wall or counter. It was a party line in more ways than one. Not only were our conversations held within earshot of the entire family, but also could be “overheard” at will by the two neighborhood families who shared our party line. Today’s technological wheel had not yet been invented. With no TV possible until I was 11, I spent a youth devoted to two things: my immediate surroundings and the people or book readily within sight. If company was called for, it walked or drove to you or you drove or walked to it. The rest of life was family, homework, housework, play or books, and my mother, luckily, considered the play and books to be equal in importance to housework.

“I’m basically lazy,” she always said, but I must repeat again that this was not true. Our house usually assumed a state of more or less perfection at least once a week. It is unclear the degree to which this was motivated by my oldest sister, who was an excellent commander. “Mom, we’ll do the dishes. Patti, you wash and Judy you wipe,” she would instruct, while she herself disappeared into her room for an after dinner nap.

I do remember a certain Saturday when each of us lay on her back or sat sprawled in a different chair reading when a knock sounded at the front door. Impossible! No one in our small town ever dropped by uninvited. Even sorties to or from my best friend’s house just two houses away from me were always preceded by a phone call. We remained silent, but the insistent knocking continued. I peeked out at the front door through the living room drapes and the eyes of two girls and an older woman all shifted in unison towards the drapes. Caught!

Each of us grabbed a different pile of garments, books, shoes or ice cream dishes from a living room surface and stashed them in a closet, drawer or cupboard as my mother answered the front door to a woman and her two daughters from a neighboring little town, just 7 miles away. They had dropped by because they were building a new house and had been told by my dad that they should stop by to see our house, which had been built a year before by a builder they were considering.

My sisters and I stayed a room ahead as my mother s-l-o-w-l-y showed them the house. I cleared dirty dishes from the last meal into the stove as my sister hastily made beds and tossed dirty clothes into closets, sliding them closed to obscure reality as the visitors probably wondered what all the banging closets and drawers were about.

This was not the norm. All of Saturday morning was traditionally spent cleaning floors, dusting my mother’s salt and pepper collection, neatly piling stacks of comic books on the living room library shelves, washing windows, straightening kitchen shelves. We were not slovenly, but neither was my mother a cleaning Nazi. Life and literature often intervened.

Now, more than fifty years later, my mother has been gone for 14 years. One sister has been lost to Alzheimer’s, the other is the perfect house keeper my mother never was. But every morning, I lie in bed writing this blog until it is finished. My favorite location for reading is still flat on my back, and I do not need to compete with my mother for my favorite reading spot on the living room sofa. Sometimes Morrie, my smallest dog, spreads out beside me, and I can’t help but think of my mother–feeling as though I’ve taken her spot–stepped into the role set for me by the preceding generation.

Yes, the day’s dishes lie stacked in the kitchen sink. There are books piled on the dining room table from Oscar’s last English lesson. Papers are piled on the desk next to my computer, a pair of shoes under each of several pieces of furniture. Bags of beads and Xmas presents purchased during my trip to Guad a few days ago are still on the counter, ready to be whisked off to cupboards or the art studio below.

But my book is a good one and Yolanda will be here tomorrow, bright and early, looking for tasks to justify her three-times-a-week salary. With no kids of my own to boss around or delegate bossing authority to, and salaries cheap by comparison here in Mexico, I have hired myself a daughter/housekeeper/ironing companion. Sometimes we stand in the kitchen and talk, letting the dust remain undisturbed on surfaces for ten minutes to a half hour more, or go down to the garden to decide where to move the anthurium plant, to just admire a bloom I’ve noticed the day before or an orchid recently bloomed that she has noticed in the tree I rarely glance up at.

Every generation cannot help but be influenced by the last, and in spite of many differences, I am still my mother’s daughter. It is in my genes to place some priorities above housework, firmly believing that this is good for my soul as well as the souls of those around me.

In response to The Daily Post’s writing prompt: “I’ve Become My Parents.” Do you ever find yourself doing something your parents used to do when you were a kid?