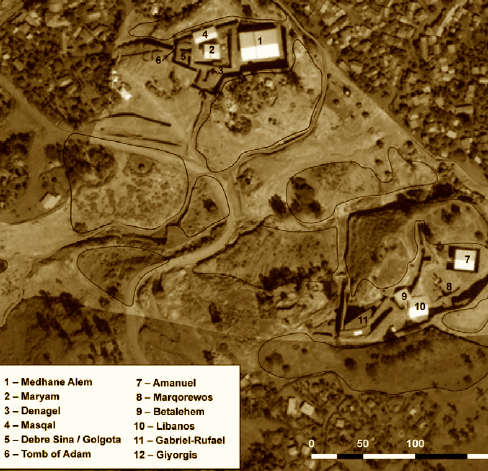

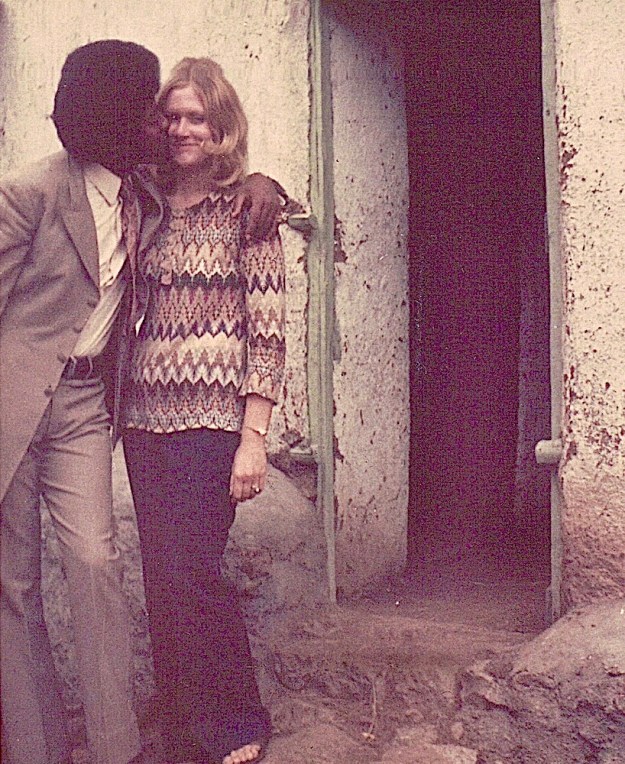

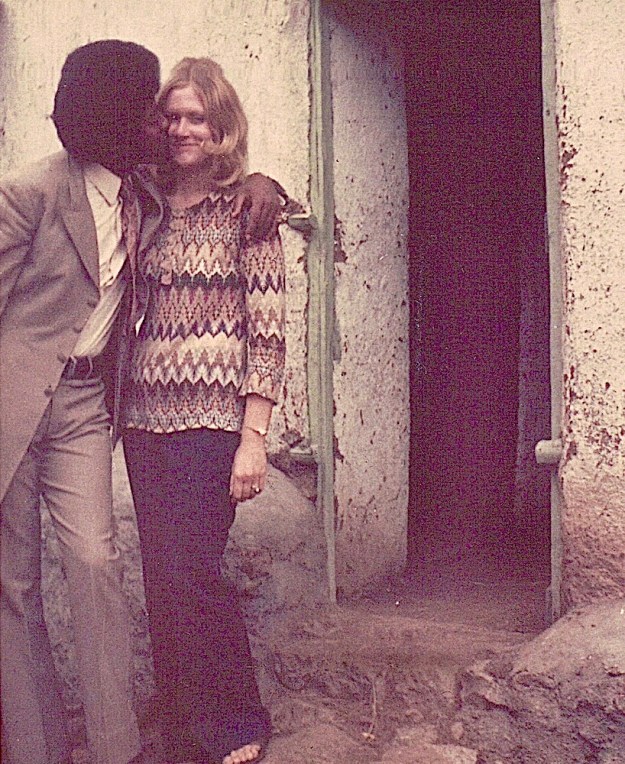

Andy and I outside our luxurious home formed of mud, manure and straw. Dirt floors. No running water. No bathroom. No electricity.

Mary has asked that I tell more of the story about the trial of the man who abducted me and the aftermath––especially about Andu Alem and why I ended up not leaving Ethiopia after this horrid occurence. I think the lady craves a happy ending, so here it is. In the past segment, found HERE, I skipped over most of the information about the trial. Here is more information as well as some of the aftermath, including Andy. It starts the morning after I was accosted by two of Solomon Kidane’s friends who threatened my life and the life of my friends if I didn’t withdraw charges against him. The story continues:

The next day I went with my attorney and we started making the rounds of government offices and officials, eventually making it up to the equivalent of the national Attorney General. The way the Ethiopian justice system works is to hear an hour or two of testimony per week for each case it is adjudicating. This can lead to very long trials—sometimes a matter of years—and businessmen learn to devote one day a week to sitting in court to plead various issues before the court. After hearing my story, however, the Attorney General granted special dispensation for my testimony to be heard in one or two long sessions or for as long as it would take so I could then be free to leave the country. The fact that he had suspended this custom for me was remarkable, explained my attorney, in that it was without precendent. A court date was set for the following week.

The day of the trial, my lawyer and the embassy interpreter picked me up in a taxi and we rode to the courts building. They led me to the courtroom, where another case was being heard. Interestingly enough, it was the trial of a young Tegrian woman who had been among the hijackers who had hijacked the Air Ethiopian plane that I have mentioned formerly. Ironically enough, she was the cause of “Solomon Kidane” and the other security guards being on my plane and so was responsible for my kidnapping as well. It is a further irony that the hijacking had been done to call attention to the revolutionary cause that Solomon Kidane and his friends were also sympathetic to.

The first day of the trial, I sat in court watching several other cases being presented. I was curious about what was being said, but remained unenlightened for all of the testimony was, of course, in Amharic. When my case came up, they charged a young man sitting on the right hand side of the aisle with the crime. When they asked if his name was Solomon Kidane, he said no, presenting his identity papers. Clearly, his attorney said, they had arrested the wrong man. The judge told him to turn around and face me and asked me if this was the man who had abducted and molested me. I was confused. Solomon Kidane had had a full Afro, whereas this young man had closely cropped hair. Could they have substituted someone else in his place? What could have happened? He looked so different. How could I be sure that this was the man who assaulted me? Then I noticed the huge goose egg on his forehead in the exact same place where I had hit him over the head with the lamp. At the same time, I remembered him showing me various i.d.’s that he had used in his role as a secret security agent.

“I am sure he is the man,” I said to the three judges hearing my case, and went on to explain to them that Solomon Kidane was just one of his many identities.

For the next three hours, his lawyer did more to prove my moral turpitude than to defend his client. Was I a virgin, he asked? How many men had I slept with. Why was I crying when the airplane left Lalibela and who were the two men who had brought me to the plane? Had I slept with one of them? I answered truthfully that yes, I had. Had I slept with both of them? No, I had not. Why was I traveling alone he asked, and did I sleep with many men as I traveled. No, I did not. Had I not propositioned this man and asked to meet his family? When he came, had he presented me with a gift? Yes, I answered. In accepting this gift, was I not expressing an interest in this young man, and did I feel it was proper to accept a gift from a man who was a stranger. It was a cheap shamma that could be purchased in the marked for the equivalent of $3 American, I answered, and I felt it would be rude to refuse. In return, I had given him a hat I had bought that had cost much more. Was I aware that in Ethiopia an exchange of gifts like this could indicate an intention to wed, he asked? No, I answered. And was I aware that abduction of a bride was still a behavior often practiced there?

“And is saying you are going to kill your bride after raping her also an established tradition? “ I asked.

At the end of my three hours of testimony, in which his lawyer did everything to discredit me and to prove my moral unworthiness, Solomon Kidane was arrested and ordered to stand trial. The judges then released me from obligation to the court.

One very interesting twist to the story is that I was in sympathy with the E.L.F. cause and felt it justified, and so I never did reveal to police, my attorney, the embassy or the judges that these men were all E.L.F. members. If Solomon Kidane was to go to jail, I wanted it to be for his personal actions, not his political ones. I believe to this day that the men didn’t realize that I could understand their political ravings as they got drunker and by the time the night was over, they had given away a secret that I was wise not to reveal I understood.

The day after my court testimony finished, I was preparing to depart for Khartoum to join Deirdre when a letter was delivered to me via Poste Restante. It was from Andy, who stated that he had heard what “that man” had done to me. “He is just devil!” he stated in his usual colorful English, and he went on to say that sending me away was the biggest mistake of his life, and that I should come back to Lalibela to live with him until they were forced by the upcoming rainy season to journey out over the mountains via Land Rover to go back to Addis. “After that, we will travel to Kenya, and then we will marry,” he said.

Two days later, I was soaring low over a familiar grass landing field. Andy and Tessie met me with arms full of flowers. How did they know I was coming? I asked. It was Tessie who answered that they had met every plane since Andy had written the letter telling me to come back. When we went to the Seven Olives that night for a welcome back celebration, I noticed that the flower garden was completely shorn of flowers. “Every day, they granted us permission to cut flowers for your arrival,” admitted Andu Alem. “By the time you finally came, we had had cut every flower.” That night, lay singers in the Tej house once again sang the song of my coming back, and staying with Andy, and opening up “The Judy and Andy Souvenir Shop.” They had predicted it, they insisted. As it turns out, the ending to our story did not turn out as foretold, but in this way I nonetheless entered into the lore of this mountain village so far removed from civilization.

(Even though the name he used with me was fictional, I have changed the false name he used to “Solomon Kidane.” Ironic that I would change a real false name to a false false name, isn’t it?)