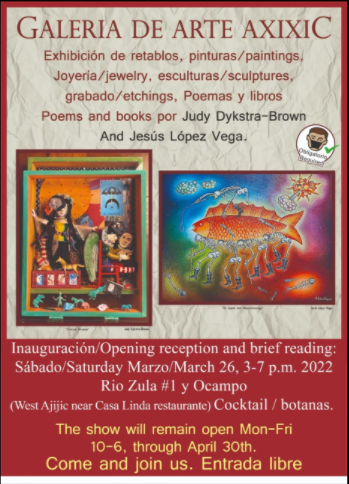

The Ojo is the oldest English language magazine in Mexico. 40 years old this year! Marion Couvillion was a nominee in another category. HERE is the story he was nominated for. Congratulations, Sam!!!

This is the article I won the award for:

Holding the World Together With Beads and Wax:

An Intimate Encounter With Huichol Art

By Judy Dykstra-Brown

The Huichols (who call themselves the Wixarika, meaning “prophets” or “healers) are one of the oldest indigenous cultures in Mexico and are said to be the one least touched by the modern world. Although it is often said that they are descendants of the Aztecs, the Huichols actually predate the Aztecs. The Aztecs themselves called the Huichols “the old ones.”

Believed to number between 8,000 and 14,000, Huichols have resided in relative isolation in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango and Zacatecas, Mexico since around 200 AD. Because they were able to retreat into the roadless and almost impassable regions of the mountains during the Spanish occupation, they are the one indigenous culture that survived relatively unchanged by the years of Spanish influence.

I became interested in the Huichols in 1992 when a PBS documentary (Millennium, series 8) depicted the story of a Huichol man who was on a pilgrimage to find a cure for his son who was ill. Years later, when I moved to the Lake Chapala area, I became more intimately acquainted with the Huichol culture through my admiration for their art.

Beaded gourds, sculpture and jewelry were originally made as offrendas or votive offerings to the spirits of ancestors. I first bought several rakures (gourd prayer bowls) covered with intricate patterns of beads. In short order, I started buying beautifully beaded bracelets, earrings and necklaces. At a show in San Miguel, I found a wonderful string painting made by spreading beeswax on a flat sheet of wood and pressing wool string into the wax, and the next year I bought another at the Maestros del Arte (a yearly Chapala show where master artisans from throughout Mexico are invited to show.) More jewelry followed.

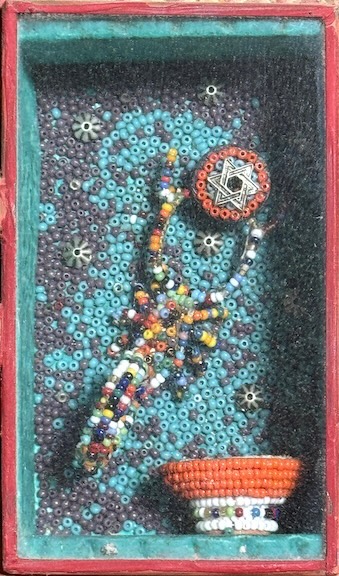

It was over a year ago that I became so entranced by the workmanship and intricate eye to detail and symbol in Huichol art that I decided to try my hand at it by incorporating the use of wax and beads into my retablos (metal storyboxes.) This is when I became serious in my research of the symbolism and ritual of Huichol art.

I learned that the scenes depicted were often the story of a particular spiritual journey along the peyote road that either a shaman had experienced and relayed to the maker, or that the maker himself had experienced during the weeklong yearly journey into the sacred peyote fields near Real de Catorce or during other peyote ceremonies later in the year.

String painting, an art form relatively new to the Huichols and produced solely for commercial purposes, still reflects ancient spiritual themes as in this peyote/snake motif.

I learned how important the relationship between the natural world and the individual spirit are to this culture that has managed to retain its traditions in spite of the pressures of the modern world. Surviving by growing crops such as corn, squash, beans and amaranth, they have also learned to supplement this subsistence-level cultivation of crops by selling their art to the tourist and gallery trade. So it is that the men of a culture traditionally given to isolation and privacy, walk the streets of cities such as Guadalajara, Durango or Mexico City in their traditional clothes intricately embroidered with the figures of peyote flowers, sacred animals or designs in the patterns of markings on the backs of snakes. (Women, more simply dressed, still wear the short full blouses in beautiful colors, full skirts and headscarves.)

Although evangelical groups who tried to supplant the traditional religion in Huichol villages found themselves ousted and their homes burned, some Catholic iconic figures have been absorbed into the Huichol culture. Images of angels, Christ and the Virgin Mary may be found in the carefully waxed boards that intricately depict in beads or string some story of Huichol myth, history or current spiritual experience; but the angels in my string painting illustrated above are beautifully robed in Huichol dress and hover over the more classic symbols of Brother deer, corn stalks, votive bowl, rain, feathered sticks, peyote button and flower.

It is possible that the Huichols were better able to tolerate some of the tenets of the Catholic faith because they found them to contain some similarities to their own culture. Ceremonies where amaranth grain was shaped into the form of a Huichol “Ancestor” and where the body was later broken into pieces for each to consume were seen to be similar to the sacrament of holy communion, and this ritual use of the grain (which was also a staple food crop in Mexico at the time) is perhaps why the Spanish forbid the cultivation of amaranth during the years of occupation. Sadly, as a result, this highly nutritional grain that also bore the advantage of being able to be stored for long periods of time, has disappeared as a staple of the Mexican diet.

As I started work on my first retablo that made use of the Huichol beading techniques, it seemed important to honor the amaranth formerly denied by the Spanish. For this reason, I worked for hours covering this plant in tiny beads meant to simulate the buds of the amaranth plant.

As I researched my topic on the Internet, I began my own personal journey through Huichol spirituality. I was already acquainted with some of their symbols such as the scorpion, deer, corn, arrows, turkey and eagle feathers, moon, sun, fire, peyote and flowers, But as usual when beginning a piece with a new theme, I felt the need to discover the meaning of these symbols. Many I incorporated into the two three-windowed retablos I was able to complete over the next four months. Since most of the symbols used were ones that had special significance to me, it was a simple matter to blend my own mythology with that of the Huichols to make pieces of double-significance.

My first efforts at beading demonstrated clearly what a laborious process it is.

A Huichol-made butterfly, three earrings and a cross give inspiration to my own beading in the rest of this piece.

I was reminded of the stories told to me by an old man who directed my steps around a local church, showing my friends and me how the Mexican stone carvers had been able to hide numerous symbols of the old religion, incorporating them into the Christian symbols demanded by the Jesuit fathers. Now I was the artisan, craftily hiding my own meanings behind the symbols common to this society where all art was either an expression of or an offering to the spirits of nature that they both sought preserve, honor and thereby to maintain a oneness with. Each of my beading tasks became an exercise both in craftsmanship and in philosophy as I tried to remember the significance of each symbol.

The deer that is so central to Huichol mythology carries for me an association with Frank Waters and his book “The Man Who Killed the Deer.” That book, which I taught in a Native American Literature course, had a great effect on my own spiritual beliefs. Its triple symbol of the deer, the eagle and the snake reveals the similarity between the beliefs of the Pueblo people and the Huichols. In the book, we are told that if you have a secret, you should not tell it in front of the snake, for the snake will tell the eagle who will tell the deer. Here, again, the interconnectedness of all creatures and parts of nature is expressed.

The deadly scorpion of the Sierra Madres, which every year causes deaths among the Huichols, nonetheless is used in their art as a protection against evil. However, as I carefully applied bead after bead to the wire form of the scorpion in my piece, I was instead remembering a jungle in Timor where I was first marooned, then stung by a scorpion and saved by the cumulative efforts of 12 traveling companions formerly unknown to me.

The small beaded clay bowl beneath the scorpion contains cornmeal and amaranth, both traditional Huichol offerings.

Positioning my scorpion into one of the three display cases of my piece, I was reminded of the constellation Scorpio, and so the swirling cosmos formed behind him, with silver beads becoming stars. His pincers seemed to be reaching out for something, so between them I positioned a stylized peyote shape, then, reached into my charm box and found a star that seemed to be just right to place over the peyote symbol to complete the tableau. I had already discovered that the Huichol star is identical to the Star of David, a fact that has caused one researcher to wonder if perhaps here was the lost tribe of Israel!

Slaving over the intricate task of beading on wax, only to have the piece heat up in the sun and all the beads reposition themselves, I developed a new respect for Huichol craftsmanship. Time and again, I put neat rows of beads into place along edges, only to have them come loose or push out of shape. Finally, I removed weeks of beadwork, scraped off all the wax and used white glue in its place.

Working in from the edges, as I had read the Huichols do, I was frustrated to find not enough room for the last necessary bead. Forcing it in, I found other beads all pushed out of shape. How in the world did they do this????

I found incorporating exquisite Huichol pieces and then surrounding them with my own work to be a wonderful and spiritual task. Slowly, stories started forming.

The deer I had painstakingly covered in wax and brown beads with black hooves, then stripped to cover with white beads, then again stripped to cover in multicolored beads, finally seemed right; but behind him, a blue sky and yellow and brown ringed circle (sun? stylized peyote button?) seemed to form itself. Then clouds demanded to roll in. Soon a tree appeared, covered in fruit, some of which had fallen to the ground. What I had intended as a bright orange sun somehow slipped down and became a bright orange hill, setting off and giving extra importance to Brother Deer, one of the most sacred symbols in Huichol spirituality.

I started examining more closely the booths selling Huichol art in the tianguis market in Ajijic. If someone was working on a piece, I looked carefully to see what tool they used to pick up the beads, what technique they used in positioning and nesting it into the wax. There seemed to be no tricks for achieving their incredibly straight lines that always ended in exactly the correct place.

I looked more closely at that my purchased Huichol pieces that had been beaded on flat boards. There were never any empty spaces caused by an inadequacy of space for the last bead. There was no awkwardness of line. I began to see the intricacy of the design, how shadow and perspective were accomplished by choice of color and subtle outlining that achieved the exact correct effect.

As I struggled over each section of my second retablo, spending a ridiculous amount of time just to cover one tiny ear of corn or animal figure, I became more and more amazed at the low prices these Huichol artisans were charging for their work. When I heard tourists in the tianguis (open-air market) trying to bargain for an 80-peso necklace that I knew must have taken a day or more to make, I couldn’t help but comment to them that the initial price was not only fair, but in fact ridiculously low for the amount of work involved.

I started to look more closely for exceptional work and to buy it when I found it, knowing that that piece would never be duplicated. I never bargained. Each piece I admired or purchased was the instigation for more research and I added new symbols to my repertoire. I discovered other sacred animals: the peccary, (javelina), butterfly, hummingbird. I discovered the legend of Amaranth Boy and Blue Corn Girl, the flood legend that seems to be central to many cultures and religions.

This expertly beaded Huichol cross puts to shame my efforts at beading. The center circle is my addition.

I found in the marketplace this exquisite small cross that had been beaded using tiny beads a quarter the size of the regular Czech seed beads which in modern times have supplanted the seeds, clay, bone, jade, coral, pyrite, shell, turquoise and stone chips used for beading in ancient times. This cross, perfectly beaded with delicate and subtle shading, cried out to be included in my first piece. It seemed the perfect symbol for what I have been learning all my life. Here in Mexico, this lesson seems to have been accelerated. That Christian symbol, beaded in a peyote design, represents to me the open-minded acceptance of similarities of all cultures. This cross, accepted and altered by this oldest culture in Mexico, has again been accepted and altered by me to fit into my own spiritual identity. It represents perfectly one thing that most of us who choose to live in a foreign culture must come to accept. Simply, that none of us have all of the answers. To become wise, all of us need to search outside of ourselves and perhaps outside of our own cultures to find the truths that all of us, ironically enough, carry within us.

We are one with nature. One with our world. What damages the world damages us. When we damage others, we damage ourselves. The Huichole’s entire life is spent in trying to maintain this balance in the world. The sun is falling? They seek to find a way to shore it up. Mother Earth is dying? They seek to find a way to minister to her needs.

Some years ago, Huichols staged a 600-mile walk to Mexico City to ask to be given 20 white-tailed deer from the zoo to establish a deer-breeding project that would enable them to reintroduce the species that had become extinct in their mountains. Seeing the absence of this species central to their religion and mythology, they feared the unbalancing and destruction of the world.

Sacred pilgrimages, week-long deprivation during the sacred peyote hunt, offerings left along the old walking paths, designs pressed into wax or strung on string or wire–by all of these means, the Huichols strive to hold their world and ours together.

Meanwhile, the modern world advances on their sacred spots. Highline wires buzz above one of the four sacred spots by Real de Catorce. Developers sought to build a high-rise hotel in San Blas over their westernmost sacred shrine. A third, located on an island in Lake Magdalena, was destroyed when the lake was drained. This small stone hut on a hill on Scorpion Island in Lake Chapala was erected by the Huichols to replace the Magdalena site. Here they deposit offerings such as maize, beadwork, chocolate, paper, pictures, letters, and woodcarvings.

Visitors to Scorpion Island can stoop down before this stone hut to see the offerings left inside.

Visitors to Scorpion Island can stoop down before this stone hut to see the offerings left inside.

We are lucky to find in our modern world the living history culture of the Huichols. They are a people to whom the spirit world is more important than the material world. For them, peyote is not an entertainment, but rather a pathway and method of communication with a world we rarely experience–a world of spirit, which is interwoven, with the outer world. When they take peyote, they find the pathway to that world. When they create their art, be it offertory or for sale in the marketplace, all of that art is suffused with their memories of the spirit world. The art itself is both a communication with that world and a record of it. Those of us who buy it as a beautiful object, get more than we are paying for. We not only buy the reflection of a beautiful culture, but with it we are given the gift of the Huichols, who for themselves and us also are holding the world together.

Author’s Note: When I began this article, I fully intended to give a detailed explanation of Huichol symbols and history. The more I delved into the research, the more I realized that this information is readily available on Google, written by people much more acquainted than I am with the Huichol culture. Instead, as in life, my article has taken a more personal path. It is hoped that it will inspire you to delve more deeply into matters of which I have merely hinted.

HERE is the article Marion Couvillion was nominated for.