I thought I had told this story before and promised to send a link to the story to Eilene , but looking through my WordPress files, I can’t find it so I’m sharing it here. This story will also be in my upcoming book, The China Bulldog and Other Stories of a Small Town Girl, but I’ll give you a sneak preview here.

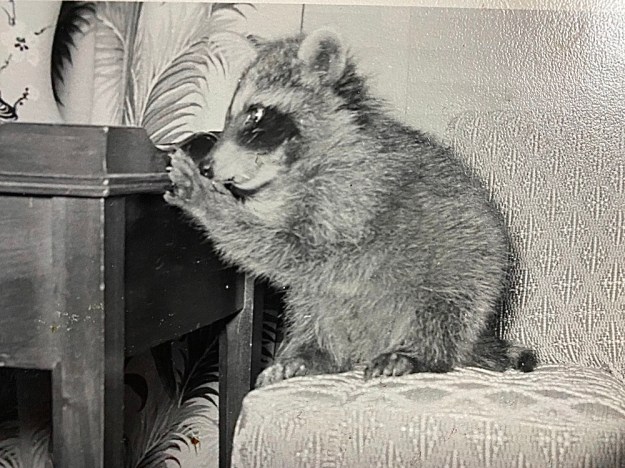

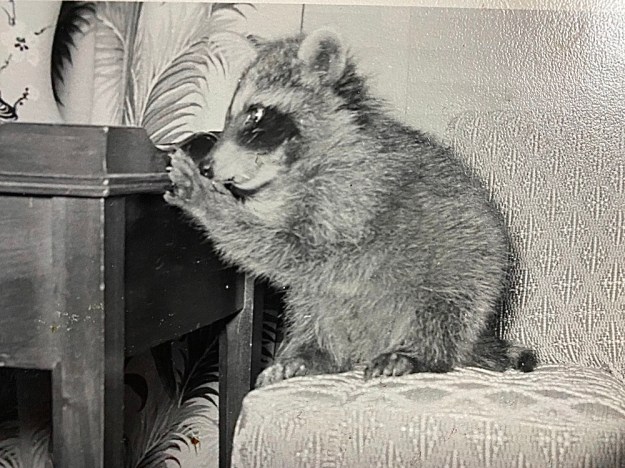

Zippy

We were gathered in groups up and down the broad sidewalk that bordered the church windows. The service was over, and people had lingered to talk away ten minutes or so before climbing into their cars and going home to Sunday dinner.

My mom and older sister had gone on home right after church–my mom to make the gravy, my sister to talk on the phone. I was talking to Pressie and Tina Ivy, but I could overhear my Dad talking to Babe Reynolds. To tell the truth, someone a half block away could probably overhear my dad and Babe talking. They were swapping stories and laughing and trying to one-up each other in both.

Tina Ivy was lying, as usual–telling Pressie and me about a boy she met at the show in White River. Pressie and I could hardly stand to think about boys, no matter how cute they were. The boys we knew were mean and dumb, and they were Murdo boys. White River boys were, everyone knew, even worse. The thing that made it hardest to believe was that Tina Ivy, like us, was only eight years old. It would be three years before any of the rest of us began to think about wanting to meet up with boys, and five more years beyond that before we started to realize the potential of White River boys. Thinking about boys at the age of eight was crazy. It was gross.

The truth was, nobody could stand Tina Ivy. But since we lived in a very small town with a minimum of kids my age, and since I craved variety at any cost, I kept trying to play with her. But she used to pinch––taking real little pieces of skin between her nails and squeezing hard–so she made marks and even drew blood sometimes. And she lied all the time–everything she said. So liking Tina Ivy wasn’t easy. On this particular day, Tina was telling lies about boys and Pressie was rolling her eyes and looking fed up, so I told Tina we had to go and pulled Pressie toward my dad. Babe was talking when we walked up. He was telling about a coon hunt they’d been on the night before–how the dogs had caught the coon and killed it before they realized that she had babies. How they’d taken the baby coons home–three of them–and had them in a box in the kitchen.

Babe is the dad of Lyle, one of the five boys in my class at school. I told you this was a small town, and ours was the smallest class in the school every year. There were just 15 of us who went all the way from first grade through high school together. In spite of this fact, we weren’t a very close class, because even though we saw a lot of each other, we also fought a lot.

Lyle’s family lived four or five miles out of town on a farm I’d never seen. Farm life to me seemed glamorous––the travelling to and from, the animals, and farm kids got to bring their lunch and eat at school while the rest of us all had to go home for lunch. The fact that my dad was a farmer/rancher did little to dispel the glamour, since we lived in town and I only got to visit the farm occasionally for very limited time periods.

But my dad did what he could to bring the farm to us. Every night when he got home, we emptied wheat chaff from his pants cuffs, scraped dried mud off his work boots with a dinner knife, dusted the dust off his broad-brimmed straw work hat or billed khaki cap. Usually, we were rewarded for our efforts, because along with grain and dirt and dust, he brought us stories of the feral cats that built their nests in the fields, of mother birds feigning broken wings to lead him away from their nests, rattlesnakes in haystacks or the tiny mole he had unearthed while plowing.

Some of these stories he illustrated by bringing home their principles: three tiny yellow kittens whose mother had been killed by the plow, a blind mole, jackrabbits too small to survive on their own, goldfish from the stock dam where they had thrived and multiplied after someone dumped a bowl of them into the pond, an injured magpie.

But a raccoon I had never seen.

“Ben, promise me that you’re not going to bring home another animal.” It was my mother speaking. We were at the dinner table. I’d beaten my dad to the raccoon story, my words stumbling over each other as I tried to give her all the details.

“And we get to go see them, Mom. We get to go see the baby coons.”

My mother, always a sucker for baby animals, protested every time, “Never again.” Every tiny grave, every shoe box lined with dandelions and worn out silk panties and filled with kittens dead from distemper or limp goldfish, every trip out to the farm to release a now-grown baby rabbit, brought these words.

Of course, she said it again. “No baby animals, Ben. No baby animals. You can go see them, but I’m not going. I don’t want to get attached so I’m not going to look and if you’re going to go look, just remember. No more baby animals.”

Five minutes later, my dad and I were bumping down the rutted dirt road to the Reynolds place. I had my feet propped on his old steel water can. It was wrapped in frayed dirty canvas that he wet to help keep the well water he filled the can with cold. The canvas was all dried out now, but I took a drink of the well water anyway, loving its tinny sharp taste. Whenever we went out to the old Millay place, we stopped to fill the can with that water–the best water any of us had ever tasted.

When we got to the Reynolds’ house, they took us into the kitchen, where the baby coons were nested up to each other in a cardboard grocery box. Lyle’s mother let me hold one, and it wrapped its black little human hands around my finger and sucked on it, like I was a bottle. It was warm and furry and gave off a strong odor of milk and wet fur and wildness. It was the closest thing to a monkey that I ever held and my heart turned over. I loved this little thing. It was better than a baby sister, which I’d been told I’d never get. It was so tiny I could hold it in my hand with only its legs dangling over. Its nose was black and sharp, its fingernails beautifully shaped like it had had a manicure, and the skin on its palms was the softest thing I’d ever felt– smoother than the silk inside my mother’s fur stole, smoother than the chamois powder-choked lining in her compact case, smoother than my mother’s face just after she’d washed off the Lady Esther Face Cream.

My mom’s real name was Eunice, but she always called herself Pat. My dad, however, much to her displeasure, never called her this. He called her “Heifer,” which she hated, or, when he was feeling more tactful, “Tootie.”

“ Toooooootie-Wootie….?” he called out teasingly as we slammed in through the back door.

“What did you do?” My mother accused as we walked into the kitchen.

My dad faced her in his innocence. We were empty-handed.

“You didn’t bring back one of those baby coons, did you?” she said.

“Didn’t you tell us not to?” asked my dad, “You did tell us not to bring home any more baby animals, right?”

“So you didn’t get one, then?” my mom asked.

“Well, you told us not to, didn’t you?” This was my dad again. I was just watching.

There was a little pause then as we all just stood there, looking at each other.

“Were they cute?” asked my mother in a softer voice.

Then I couldn’t be quiet anymore. I told her about their fingernails, their breaths, their soft coats and softer palms. I told her how they fit in my hand with only their legs hanging over. I told her she should have seen them and she said she wished she had, but that she’d just get attached and that it would make it harder not to take one and how she’d decided: NO MORE BABY ANIMALS and so she’d just rather not look.

My dad went out then and came back with the cardboard box. I lifted out the baby coon, whose eyes were closed even though he was waving his body around.

“Oh Ben, you didn’t!” She was holding the baby coon, though, and she was smiling.

She sent me for one of the doll baby bottles and when I came running through the kitchen with it on the way from my upstairs bedroom to the living room, where I’d left them, I ran into her at the kitchen stove, warming milk.

His mouth was so tiny that only a doll bottle nipple was small enough to fit. He made hard sucking noises and drained the bottle very fast, wrapping his hands around my mother’s finger as he nursed. I ran back to funnel more milk into the tiny glass bottle, then worked the rubber nipple on as I ran back to the living room. After another bottle, he fell asleep, his fingers still gripping my mom’s hand. When I bent over him, the hot fusty pee smell of his fur mingled with a slightly rancid milk breath. His mouth made little sucking motions, like he was dreaming about even more to drink. My mother was smiling.

“We can take him back if you want us to, Tootie,” my dad said.

***

We named him Zippy for the way he liked to unzip and zip my dad’s jacket pocket, looking for treats. For the way he moved fast under the beds, up the shelves. For the way his tiny kidskin paws slipped like eels into hidden places. Zippy for the smooth way his mind worked as he figured out solutions to each new puzzle that life presented him with.

My mom used to dress him up in doll clothes and wheel him around in our baby carriage. As he got bigger, he graduated from holding her finger to holding onto her wrist as he nursed. Finally, he got so strong that when she drew the bottle away, he would twine both feet and both hands around her wrist, dragging the bottle back down.

The first week we had him, my sister and I would fight over who got to give him his morning bottle, but after a week, she began to be diverted by the kids swinging in the schoolyard across the street before school started, and she was off like usual to claim the best swing before all the other kids got there. Never having had a baby sister, like she had had, I was not so easily diverted.

Soon he was crawling up the floor-to-ceiling built-in shelves in the living room, maneuvering carefully around Patti’s salt and pepper shaker collection, reaching his hands into the cornflower blue urn on the top shelf.

It was my mother’s pride that every one of her girls had walked by the time she was ten months old and was potty-trained soon after. In like fashion, she had litter-box trained every bunny, puppy or kitten that my dad had carried guiltily home for her to nurse, feed, train, groom, clean up after and love. Even our parakeet Chipper, the only animal we ever had that was actually purchased in a pet store, had been trained by my mom to fly into his cage whenever nature called. So it was no surprise that Zippy, from his first week in our presence, was trained to use a litter box.

As he grew, he graduated from doll bottle to baby bottle to milk in a bowl and raisin bran that he mined from “his” box in the row of cereal boxes that stood lined-up on a bottom shelf of one of the kitchen cupboards. If we didn’t wake up early enough, he knew which of the numerous cereal boxes was his and he would climb up to hang off the side of the box as he reached one arm in to gather raisin bran. At first, he was so tiny that as the level of the cereal went down, he had to reach farther and farther into the box, until finally he was clinging onto the edge of the upright box with his hind legs with most of his body hanging down into the box as he reached for the morsels at the bottom. When we replaced the box, we put his new opened box in the same position–last cereal box on the left–and he proceeded to eat from only it–only the last box on the left and only raisin bran. If we put our own box of raisin bran right next to it, he would not touch it.

When my dad got home from work at night, Zippy would be the first to greet him at the door. Before my dad could get off his overboots or unzip his parka or take off his cap, Zippy would be climbing his pants leg and perching on his shoulder. He’d start tugging at the zipper on the parka, and as my dad took off his coat, he would move to cling from his shirt front as he slid the coat off his shoulders. Then back up to his shoulder he would climb, reaching into his pockets for treats. If the pockets yielded no treasures, he would search ear holes, nostrils, pry open my dad’s mouth and teeth to search even this secret place. Once when my dad squeezed his eyes shut, he even pried open his eyelid. Always, though, in some hidden place––his zippered coat pocket or the top of his socks, my dad brought some surprise, even if it was a piece of dried cat food picked up from the dish of the outside cat on his way up the backdoor steps. More usually it was candy or gum or, in dire circumstances, a Bisodol antacid tablet.

Every animal that came to our house was my mother’s baby. We had a bunny once who used to hop around under the train of her long robe––a hopping lump of quilted velvet, following her all over the house. Our parakeet learned to speak in her voice, always cued by the school bell which was calling us into the school across the street as consistently as it was drawing my mom with a second cup of coffee and a cornmeal muffin into my dad’s vacant rocking chair––the most comfortable chair in the house––which just happened to be situated right next to the birdcage. Then woman and bird would talk for a half hour or so, using the ever-expanding vocabulary taught to him by my mother.

“Baaaaaaad Benny,” one would say to the other.

To which the other would answer, “Hi, Chipper. Pretty bird. Gee you’re cute. Gimmee a kiss!” This line was always followed by five kissing sounds.

“ Hello, Betty Jo.”

Would be answered by, “Patti Adair: or “Judy Kay, Judy Kay.”

But Zippy was a baby not only to my mother, but to each of us. He entered my Dad’s stories every day as he took coffee with other farmers and ranchers at Mack’s cafe. His was the first story that was told to each arriving family member at night.

“Know what Zippy did?”

“So, how’s Zippy?”

“Where’s Zippy?”

“Zip? Where are you boy. Here Zip.”

He was only a story to my sister Betty Jo, away at college in a state so far away that she only came home for Thanksgiving, Christmas and Summer Vacations. And by the time she finally saw him, he had grown so big that he scared her and we had to lock him in the basement whenever she was around. To tell the truth, it was kind of a relief when she went back to school so Zippy could come be a regular member of the family again. He was friendlier than my sister and more fun since she’d taken on college airs.

When Zippy was a few months old, I came home itching from school. Within the hour, I’d broken into livid red spots which my mom said were measles and which she told me not to scratch. She put me in the only downstairs bedroom—which was my parents’ room––so she could more easily care for me. It was agony as I lay in that dark room so my eyes, made vulnerable by the measles, wouldn’t be damaged and with my arms on top of the covers so I wouldn’t be tempted to itch. Bored and miserable, I begged my mom for constant company––begged her to read to me outside the bedroom door––out in the kitchen, where there was light. This was in a time before television––a time when the only radio was a huge console in the living room––but my mother brought in Zippy, bathed and powdered, and he immediately climbed under the blankets and under the sheets, pushing up tunnels of covers like a mole pushing up dirt. He’d run from one side of the bed to the other, jump down, run under the bed, back up under the covers on the other side, across the bed again, in an ever more frantic cycle. Then he’d poke his head out and cuddle up to my sore face with his soft hair. Reach up to my forehead with a graceful black delicate hand. Touch one red berry on my brow, then another. Then he was under the covers, locating each new red patch on my legs. Itching first one, and then the next, delicately, softly, exquisitely quenching the itching that no amount of calamine could cure. All afternoon long and all the next day, he stayed with me, itching my itches under the covers where my mother couldn’t see. Me with my arms folded on top, as she had directed. She’d bathe and powder him three times a day to keep him fresh, then sponge my legs and chest and arms with water and baking soda. She’d read to me outside the door, or my sister Patti would read. But Zippy was my most indulgent nurse. His hands, ever gentle and curious, ever vigilant, knew where I itched. His soft fur knew where to place itself against my neck and face. His energetic body knew how to entertain a bored eight-year-old. Outside the door, it was my sister Patti reading to us “The Little Prince,” but under the covers, it was Zippy and me. Our secrets.

When my sister Betty Jo came home for Christmas vacation, Zippy was again relegated to the basement. And this time when I’d go down to look for him, I couldn’t always find him. He’d climb the water pipes and wedge himself into corner spaces between merging pipes right up against the basement ceiling. And even when my sister left, we couldn’t get him to come up again, except for food every once in a while, and then he’d return to the pipes in the basement. My dad explained that he was hibernating, but I was sure that he was miffed. My sister, barely a relative any more, had been placed before him––my ever-vigilant friend. I couldn’t blame him for having his feelings hurt, but I missed him and wanted him back.

In mid-January, we all drove in the car to Pierre and went to a big store that had a room filled with toilets and tubs and sinks and hot water heaters. My mom picked out a creamy yellow bathtub and toilet and sink, and the next week Mr. Chambers came to rip out our old bathroom and put these modern fixtures in. My dad and our hired man, Wes, helped him carry the old tub out and the new beautiful yellow tub in. We were relieved that the new tub fit in the old space–snugly, but it fit. Then we all left as Mr. Chambers climbed into the tub to frame and caulk and tile. Next came the chrome around the drain. I imagine him now as he was then in his pillow-ticking overalls, bending over the drain.

“Jeeeeeesus Christ!” screamed Mr. Chambers, hitting the door full face, then bouncing off it to open it, running through the kitchen and out the front door.

All of us ran from every part of the house we’d wandered to. My mom from the bedroom, me from the front porch, where I was playing jewelry store, my sister from in front of the radio in the living room, my dad from the kitchen where he was sizing up prospects for a snack.

Into the bathroom we streamed, scanning the room with our eyes before focusing on the drain hole in the new tub. Up through it was poking a small black hand–like a devil hand–carefully feeling around the edge of the drain hole, then reaching up to pat the cool enamel–moving in concentric circles: pat, pat, pat. Never the small demon that Mr. Chambers imagined, Zippy had been perched in his pipe maze “tree” when he had seen the light shining from above through the unconnected pipe hole and reached up to investigate.

We found Mr. Chambers in his truck outside. We explained and even brought Zippy out to meet him. Later, he pretended that he was just pretending to be scared of Zippy, but in our stories, every time we told this story, he ran farther, ran faster, yelled louder. Until finally, he never came back.

When Zippy came out of hibernation, he was the same as ever except for the fact that he was very very big. When my sister came home for summer vacation, he scared her so much that she could not even stand to be around him on a leash. This was ridiculous, but not as ridiculous as the letters she’d been getting from boys––letters that she kept in a shoebox-sized locked cedar box that I knew how to find the key for and that I’d begun to be able to decipher, even though they were written in cursive.

When we took her back to school in late August, my mom decided that Zippy was old enough to look after himself. We left him on our enclosed back porch with three loaves of bread, a box of raisin bran and a roasting pan full of water. From the porch, he had access to the basement down the L-shaped basement stairs. We’d be back in three days. Aunt Stella would check on him every day to replenish his food supply. After electing to hibernate for months the past winter, how could he object to a few days absence on our part?

We were ten minutes down the road when my mom remembered something she’d forgotten. This was a family tradition, so there was no question that we wouldn’t simply turn around and go back for it. My dad drove up to the garage, which was behind our house, and she ran into the backyard and up the back steps. Three minutes later, she was back again.

“Come on, everybody, you’ve got to come see!”

We trooped after her, up to the back porch, opened the door.

“Don’t go inside!” she warned, “You might slip and fall.”

We peeked inside to find a floor entirely covered with a thick white paste. In less that half an hour since we’d left, Zip had taken each slice of bread out of its wrapper, dragged it through the water in the roasting pan, and plastered it to the floor, grinding it into a thick mush with his talented hands. Three loaves of bread–every piece applied to the linoleum. Almost every inch of the porch covered.

By the time I was in the fourth grade, Zippy was so well “trained” that I could take him to school on a leash. He would lead like a dog. Do dignified tricks. Sit when I told him to sit. I took the cereal boxes so they could see how disciplined he was. His box was empty. He checked it out carefully, upended it., checked it now and then throughout his entire classroom visit, but never touched one of the “family boxes” full of cornflakes and puffed oats and even Raisin Bran.

When I took Zippy home, I put a new Raisin Bran box in his place, returned the other cereal boxes, ate the big noon dinner with my mom and dad and sister, and returned to school. It was when I got home from school that my Mom and Dad told us about the new house. It was to be a ranch-style house, modern and big and just a block away, in the corner lot kitty-corner across from the school. It would have wall-to-wall carpet except for the bathroom, which was yellow-tiled with turquoise tub and sink and toilet. And the kitchen, of course, which was to have linoleum which coved part way up the walls so there’d be no cracks to collect dirt.

First there was the drama about the fact that I couldn’t have linoleum in my room. I loved my green linoleum, which exactly matched the green flowers on my yellow flowered bedspread, curtains and vanity table cover. I had to have green linoleum. I demanded green linoleum. But carpet it was to be.

Then there was the fact that there were to be no second story rooms with dormer windows to climb out of onto a sloping porch roof. No access to the roof. No place to sunbathe or have picnics or to observe baby birds in eavestrough nests. No high perch to torment Bobby Larkin across the street from or to throw water balloons from or to torture Susan Thatcher from by telling her Pressie could come up, but not her.

Fluffy, our outdoor tramp cat, might not find us a block away, I worried, a fact which turned out to be true. When we finally finished the house and moved, he became the cat of the family who bought our old house.

As it turned out, we all loved the new house–which we moved into a year and a few months later. But one aspect of the new house spelled tragedy. Zippy, I was told, would not be moving with us. He was too big, my mother argued. He needed to be in the wild. Dad knew a family out in the country who wanted him, he said. They had big trees he could climb in, or he could live inside with the family. They had three high school or college-aged sons, he said. They would play with him. They came to see him and admired all his tricks. They were excited to have him come live with them.

I didn’t get my green linoleum. Never again did I taunt Bobby Larkin from the roof of a house. I never owned another cat until I was a home-owning adult with all the attendant powers, and, in fact, Zippy never moved to the new house with us.

His adventures continued for many years, but only one of those adventures was to be experienced in our company–and that final adventure was, alas, a sad one. We were at school. Dad had decided to take Zippy out to his new home before we got home, to avoid the drama of that potential heart-wrenching scene. He had come home in the afternoon with one of the Smith boys and with Wes, the hired man. My mom, in the house, did not know that they were there to take Zippy. Wes had come at him with a gunny sack, lunged for him and missed. My dad had tried and missed, chasing Zip once around the outside of the house. Zippy by now was of a formidable size and weight. In his winter coat, he was perhaps a foot and a half wide and two feet long. He was fat–almost too heavy for me to lift. Yet, although he’d outgrown doll clothes long ago, he would still ride around in a doll carriage in my old baby clothes, and he’d still nurse from a baby bottle, play hide and seek, and try to climb my dad’s leg. He’d never shown a vicious side except in mock play, chasing us in tag from the floor to the bed to the floor–growling in make-believe anger, much as my dad did when he was chasing us around the house–playing troll to our three billy goats gruff.

By the time we got home from school, Zippy had taken sanctuary under our large front porch. Two of the men had rakes and hoes, trying to use the handles to prod him out from under the porch. They were calling out, making what must have seemed to Zippy to be threatening movements, and he was cowering in the far corner of the porch, on the foundation side near the trumpet vine. We could see his shining eyes in the darkness. I yelled, my sister cried, and my mom came running out.

“They’re hurting him!” my sister cried.

“They’re killing him!” I screamed, ever the drama queen.

My mother ran down the steps, scolding, “Ben, you’re scaring him to death. He doesn’t know what you’re doing. He doesn’t even know Hank and Wes.“ She was as upset as we were as she moved around behind Zippy, then reached out for him from behind. His eyes still focused at the two unknown attackers with prods, Zippy spun around and attacked, biting my mother severely on her arm. My mother, a bleeder, was spurting blood, my dad was shouting, we were crying. The minute Zippy recognized my mother, he was out from the porch, gentle again. I held him in my arms as my dad rushed my mom up to Doc Murphy’s office for cleaning, ointment and a tetanus shot. When they came home, my mom and dad got in the car and took Zippy out to the Smiths. All of us were sad, but my parents vindicated in their belief that Zippy was a wild animal that should be in the wild.

That was the last time I ever saw Zippy. For some reason, every time I thought to ask to go visit him was a bad time for my Mom and Dad. And the Smiths lived too far out of town to ride my bike out to their place. So Zippy’s final chapters proved to be hearsay, only. On Saturday nights in Mack’s cafe–after the show let out, or around tables filled with farmers and ranchers in for their afternoon break, my dad heard Zippy stories: new tricks the Smiths had taught him, how he lived inside with them just as he had with us, how smart he was, messes he’d made, new games he’d learned.

It was like we had a brother who’d been given away and never seen again. Yet we accepted it, my sister and I. There was, for a long while, the excitement of the new house–first the long months of the construction, then carpets and curtains and new furniture to pick, colors to choose, flowers to plant. In the sixth grade now, I knew what Tina Ivy had been talking about. Thus, Zippy slipped under the surface of our memories–less clear with each passing year so that I can’t remember exactly when the final chapter occurred. When I was in high school, perhaps, or maybe a story told when I was home on vacation from college. How the Smiths left to go to town. How they unintentionally shut Zippy up in the bathroom with no open window to climb out of. How they had looked for him when they came home, “Zip. Here Zippy.” How they finally found him in the bathroom–hunkered in the middle of the floor over a huge pile of tiny tile pieces. How he’d picked every inch of newly-installed bathroom tile off the floor, tearing off the tiles in quarter-sized chunks. How Mister Smith threw a shoe at him and Mrs. Smith opened the bathroom window, which Zippy dived out of into a nearby tree. How Mr. Smith called him that gol-damned coon ever after. How Zippy lived in the tree for a few months, never again gaining access to the house. How one day he was gone. Coon tracks around sometimes, but they never knew for sure that it was him.

All animal stories end more quickly than we would wish them to. With their shorter life span, it is inevitable. Some stories end with a shoebox lined with dandelion chains, some with a dead goldfish flushed down a toilet, others by watching a grown cottontail disappear into an alfalfa field, but Zippy’s story just faded away without an ending. Like the stories of people we lose touch with. Like the stories of people who move up or move on in life. Like the stories of people who pass from being friends into being just another story in our lives.

It is the difference between a present friend and an old one, like the difference between your next-door neighbor and the neighbor who has moved away, like the difference between the child who lives across town and the child who lives cross country. It is the difference between intimacy and familiarity, acquaintance and crony, the difference between pet and wild animal. How the story ends–with what degree of certainty and truth and detail and affection–depends upon this perspective: how long ago, how far away?