The Summer Home

THE SUMMER HOME

When my dad bought the land

where the Big White River and Little White River joined,

I couldn’t believe that we owned land with trees on it.

While he plowed the small field,

I walked the woods and found the abandoned shanty.

Its door was open; in fact it could not shut.

Inside was a mysterious, sweet and fecund smell–

a mouse smell new to me

that I couldn’t stop myself from breathing in.

The mildew and the dust,

the musk of warm linoleum,

every new smell and sight was magic.

I was enchanted by this house emptied

of chairs and tables and beds,

yet full of the accumulated energy of past tame lives

and present wild ones:

the moving of leaf shadows

across the chipped linoleum of the L-shaped kitchen,

the dents on the floor where the kitchen chairs had set,

as though someone had taken care each day

to line up the legs in their holders.

Upstairs I found crayon scribbles halfway up the wall–

the arm reach of a three-year-old.

When I asked about the house,

my dad said that it was our summer home,

and the next time we went to the field,

I brought a broom.

I cleaned out the mouse droppings and the tumbleweeds.

I collected the peeled tile fragments,

imagining gluing them back again.

I washed out a quart canning jar at the pump

and filled it with spring water

and sweet clover,

putting it on the floor

between the kitchen chair holes

in the exact middle of the vanished table.

With the old shirt I found in the corner,

I rubbed mud and river sand

from the linoleum counter tops.

More sand worked as Ajax to scrub out sinks.

All summer long I worked on our summer home,

and for that summer and many summers to come,

I waited in vain for our move to the river house.

I sat on its screened front porch.

Outside the screen grew spearmint and peppermint.

On the top leaf of the tallest branch was a grasshopper,

the kind that left tobacco stains in your hand

when you held it.

All around me were the trees–

the swaying shedding cottonwoods

and scrub chokecherries.

It was a wealth of trees I’d never seen before

in the town where we lived on the bare prairie

nor on the roads we traversed for hundreds of miles

to see a movie or a dentist

or to buy clothes.

Around the screens buzzed the heavy flies,

their motors slow in the heat of July–

all the flies on the outside

wanting to get in

and all the flies on the inside

pressing the screen to get out–

like I longed to get out

to the freedom of trees

where black crows

and dull brown sparrows

rustled their wings

and flew from branch to branch.

In the distance, meadowlarks called

the only birdcall I ever recognized.

No squirrels, no chipmunks; but, rabbits? Yes.

My father said no bears,

but he’d told me the story of Hugh Glass,

mauled by a bear,

walking this river for a hundred miles

past this very joining of the Big and Little White,

in search of help;

and I could imagine one last bear or two

hidden in my woods.

So at night, at home in our winter house in town,

when he told the story I loved the best,

I was the one who discovered the bears’ cottage,

and the cottage was our summer home.

The chairs–too hard, too soft, just right—

I sat upon in turn,

taking great care every time to nestle each leg

back into its correct place on the kitchen linoleum.

And when I lay in the perfect bed of the little bear,

I could touch the crayon markings on the wall.

So when the three bears found me asleep

in the little bear’s room,

they weren’t really very scary;

but I ran anyway,

into my dark and shadowed owl-calling woods,

my woods still echoing the day lit fluted calls of meadowlarks,

their music shaken from the snarled leaves

in the evening breeze.

I ran to trees–

their leaves frosted by moonlight and the Milky Way,

vibrating with the power of the Big Dipper and Orion,

the Seven Sisters and the North Star.

Into the trees

to where I stored my memories

in the frog-croaking depressions under clumps of grass,

in the tangles of Creeping Jenny

and the fluff of dandelions,

in the sand hollows

that crept up from the riverbanks,

in the cocklebur and the chigger-infested grass,

in the crooks of cottonwoods and caves of thickets,

in the tiny cupped palms

of sweet clover and purple alfalfa,

in the wheat grass and the oats and trefoil.

The year my dad decided to expand the field

on the river bottom,

I pleaded, I cajoled, I promised, I prayed

for the summer home

where I had lived for neither one summer

nor one night, in actuality,

but where, nevertheless, I’d had faith

I would someday live.

Of course, there was no saving the woods

and summer house.

It was rich river land, prime for irrigation.

The trees were a waste of soil.

The summer home–everybody’s gentle joke on me.

After the cats and bulldozers were through,

I went with my dad to see

where trees had been ripped out,

the house burned to the ground,

the soil turned and planted

with crops that would build the land.

Their woods now furrowed soil,

the crows and sparrows

had gone to some other shaded place;

the mice, back to the fields.

My former references of trees forever gone,

the present references of sky and fence posts

too wide and new,

I wasn’t sure where my summer home had stood.

The house’s ghost destroyed by the bright sunlight,

the woodland paths replaced by tractor treads,

I watched instead a meadowlark

soar over brown fields and settle on barbed wire,

claiming the new field for its own.

With no house or forest left,

my only shade was chokecherry bushes,

my only chair, the pickup running board.

And so my summers at the river

vanished in the smoke of my summer home

and smoldering tree stumps.

But every night, my woods again threw still shadows

over the summer house,

and I ran once more the corridors of moonlight

cut through dense trees

like parts in a small girl’s hair.

I ran in the wet dew of the condensing summer heat.

I ran on the fuel of my need for magic

and wildness

and rivers

and trees.

I ran fueled by my need to be with something

that lived outside my window

as I passed long nights in my winter house.

It lay in the dark tapping of the trumpet vine branch

against my window

and the crunching of gravel

as someone walked by on the unpaved street–

out past midnight and I couldn’t tell who.

It lay in the pricking of the hair on my arm

as I stuck it out from the bed

and pressed it to the screen.

Always, in town, it lay outside of me–

except for when I floated the paths

of the woods surrounding the summer house,

joining it in dreams,

night after night and then less frequently

until the dreams came once a month

or once a year–

in darkness, always recognized;

but nonetheless forgotten in the light.

So by the time I saw the river field grown lush with corn,

I was a teenager in my first grownup swimsuit,

floating the milky Little White in an inner tube,

down to its junction

with the clear and colder-running water of the Big White,

my best friend next to me,

our cooler full of Coca-Colas and ham salad,

our conversations full of boys and music.

At the border of the field, to get to the river bank,

we crawled over the border of large tree trunks

laid horizontal, half-buried in sand.

I guess I knew they were the bones of my midnight woods.

I guess some part of me felt

the ghost of my summer house.

But, as I lay on my back on the submerged sand bank,

the warm water flowed so sensuously over my shoulders

and down my legs

that my suit seemed to peel itself

from my shoulders, breasts, thighs, calves.

And in a dream I floated the muddy water

of the Little White,

turning in the current

until the water seemed to flow inside of me,

floating me down

to the cool clear water of the Big White,

farther and farther away

from the summer home.

This poem was posted specifically as a response to THIS post on Red’s Wrap.

“The Summer Home” is excerpted from Prairie Moths–Memories of a Farmer’s Daughter, which is available Available on Amazon in Print and Kindle Versions and at Diane Pearl Colecciones and Sol Mexicana in Ajijic, MX

Just as moths rise from prairie grasses to fly away, so did the author yearn to be free from the very place that nurtured her. Judy Dykstra-Brown’s verse stories and accompanying photographs give a vivid portrayal of rural life in the fifties and sixties, evoking the colors and sounds of the prairie and the longing a child with an active imagination feels for faraway places. From a small child curled up on the couch listening to her father’s stories of homestead days to pubescent fantasies of young itinerant combiners to her first forays into romance in the front seat of a ’59 Chevy, her memories acquire a value in time that she did not acknowledge while living them. Lovers of good poetry and those who miss the magic of childhood will relish Prairie Moths. (Excerpted from a review by Harriet Hart)

You need to CLICK to expand this one. Although this looks like a panoramic shot, it is actually a cropped version of the photo below. I think the horizontal imagery of the photo (in which every element is horizontal) is brought out with more effectiveness in the cropped version, perhaps because the canvas itself is more extremely horizontal. Unlike leading lines that demonstrate perspective by leading the eye back into the photo, these lines draw my eyes back and forth, so I wonder if they qualify as leading lines or if perspective is a requirement.

You need to CLICK to expand this one. Although this looks like a panoramic shot, it is actually a cropped version of the photo below. I think the horizontal imagery of the photo (in which every element is horizontal) is brought out with more effectiveness in the cropped version, perhaps because the canvas itself is more extremely horizontal. Unlike leading lines that demonstrate perspective by leading the eye back into the photo, these lines draw my eyes back and forth, so I wonder if they qualify as leading lines or if perspective is a requirement. (This is the original of my cropped version favorite above it)

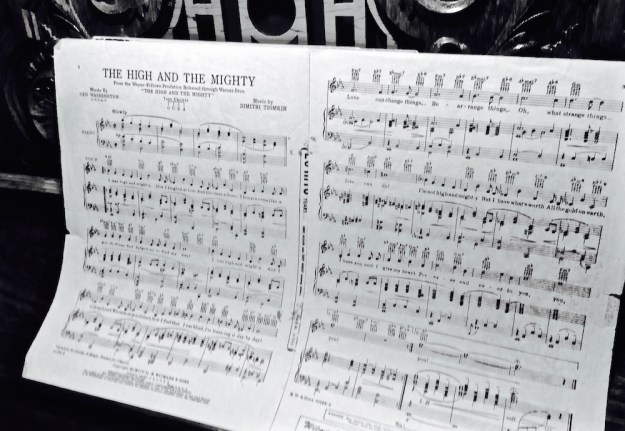

(This is the original of my cropped version favorite above it) I almost didn’t use this photo because of all the contrasting round and curved shapes, yet I feel in spite of them the horizontals of the music draw the eyes back, especially because of the narrowing perspective. I’m interested in what Cee has to say about this.

I almost didn’t use this photo because of all the contrasting round and curved shapes, yet I feel in spite of them the horizontals of the music draw the eyes back, especially because of the narrowing perspective. I’m interested in what Cee has to say about this. I love this scene and took it from about 5 different perspectives and focal lengths, including a shot that reveals shoreline for miles up the beach. There is something about the simplicity of the wave line in this shot echoed by the ripples on the sand that made me like it the best. Showing this line extending for miles seemed like overkill.

I love this scene and took it from about 5 different perspectives and focal lengths, including a shot that reveals shoreline for miles up the beach. There is something about the simplicity of the wave line in this shot echoed by the ripples on the sand that made me like it the best. Showing this line extending for miles seemed like overkill. Searching for leading lines in my current library of photos on my computer made me realize that I really do concentrate on curves and more rounded shapes. What lines I found were almost always of roads or beaches, so it was fun to include these raindrops on the windshield of a speeding car. They seem to fulfill the assignment to me, but still I’m interested in what Cee has to say about them.

Searching for leading lines in my current library of photos on my computer made me realize that I really do concentrate on curves and more rounded shapes. What lines I found were almost always of roads or beaches, so it was fun to include these raindrops on the windshield of a speeding car. They seem to fulfill the assignment to me, but still I’m interested in what Cee has to say about them.

The

The