Hail, Hail

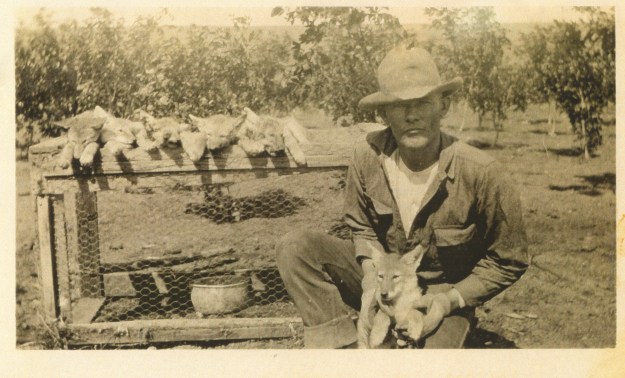

My farmer/rancher father’s boots grew older with him, their wrinkles—like the back of his neck—born of weathering: rain, snow, mud and hot Dakota sun. They were so much a part of him that when he died, they were all my pre-teen nephew asked for, and he wore them out the rest of the way, until the soles peeled back and the leather with patina already long worn off, began to crack along the wrinkles and peel off.

Those boots reflected my father’s life, where things wore out. His clothes, his favorite chair—none were replaced for aesthetics or style alone—this practicality motivated neither by penury nor cheapness, but by growing up in a house where “making do” was a necessity.

But as in most things, there was one defining vain compulsion in my father’s life that broke him free from his mold. He loved new cars, as much for the pleasure of making the deal as for the smell of new leather and metal. The car dealers learned to call him when they got a car fully loaded, the way he liked it: automatic windows, power steering, power brakes, seats that tilted and slid back and forth and up and down by the touch of a switch. Whatever automatic feature was new that year, my father was up for it—big cars with fins, when they were in style, of every color.

The car salesmen would wait until the wheat crop had been harvested and then make the call, driving the car for sixty miles over the prairie to bring it to him for his perusal, like a new bride brought to a shah. They knew him well, and so when the bargaining began, they would accept his peccadillos. It was not the price he quibbled over, but rather the trade-in. “Well, I’ve got a combine that I need to trade in.” Once, three horses. And they learned this joy of trading was often what sealed the deal.

Later, when my sister married, her husband claimed my dad traded in his cars whenever they needed washing, but this was not true. Three years was a car’s usual shelf life, before he’d hand it down to whichever daughter of driving age needed a car the most. Packards and Cadillacs and Pontiacs were his choices of brands. For some reason, he reviled Fords. So that July of my thirteenth year, when the salesman brought the bright green Oldsmobile for my dad to view, we were sure this was the car he would turn down. My mother was not sure about the color and my dad was not sure about buying an Oldsmobile. He had no real reason. It was just a brand he’d never considered before, but it had all the bells and whistles. I think it was the first year that cruise control was offered, so it possessed that allure of new technology. And so it was that the car made it past any first inhibitions on both my mother’s and father’s parts and when the salesman drove away, it was in our “old” Cadillac and the shining green Oldsmobile became the new resident of our garage.

My oldest sister was married and gone, my middle sister seventeen—a year past legal driving age. Summer camp in the Black Hills was nearly 200 miles away, but over easily-navigated straight roads through bare prairie, the wheat having been cut early that year. So it was that my mom, worn pliable from 20 years of driving daughters hundreds of miles to doctor appointments and eye appointments and ball games and church rallies and singing contests and summer camps, decided my sister could drive me to camp that year.

My sister Patti and her best friend Patty Peck piled into the bench front seat. My best friend and I piled into the back. The trunk was full of two weeks worth of camping clothes. The pleasures of riding in a brand new car, just one week removed from its purchase, equaled the thrill of being off on our own. We rolled down the windows, stuck out our arms and let the hot July air stream through our fingers, stopped at Wall Drug for milkshakes, sang at the top of our lungs, and when our bare legs started sticking to the vinyl seats, closed the windows and enjoyed the air conditioning.

Three hours later, the black outlines of the hills that were our destination grew close enough to define the ponderosa pines that gave them their name. We cruised past Rockerville Ghost Town—a tourist trap where my oldest sister had worked a few years before—and turned off into Coon Hollow. My sister steered the car carefully over the dirt roads, fearing chipped paint or a chipped window from the occasional rock in our path. “Take Me Back to the Black Hills” we crooned, as we always did when we approached our favorite vacation spot. We rolled down windows once again to enjoy the scent of ponderosas and to hear the gurgling of the water as it rushed down the small river that paralleled the course of the dirt road that led back to the campsite.

“Black Hills Methodist Camp” read the sign. We stopped to take a picture before veering off onto the divided dirt road, and we had just caught site of the large log cabin that served as the mess hall when the first loud “Whump!” occurred. Then another and another and another. Terrified, my sister steered the car off into the trees as the hail grew larger and larger. We were facing the creek, which had grown wild with the churning of the hailstones hitting the water. They grew rapidly from quarter-sized to golf ball-sized to baseball-sized. The front window began to shatter. When one large hailstone seemed to pierce the roof of the car and land in my lap, I was out of my seat and over the back of the front seat onto the seat between the two Pattys before I could even think about it. As I remember it, I somehow managed this shift in position without ever removing my seat belt, but this, perhaps, is an exaggeration that occurred more in memory than in actuality. My friend, still in the back seat, held up the white ceiling light cover that had popped off when a huge hailstone had hit directly on top of it—showing that the rooftop was still unbreached

The entire hailstorm probably occurred over no more than a ten-minute period, but at the end of it, the stream in front of us was completely white with floating hailstones and the ground was covered. We climbed from the car, pushing through the hailstones in a shuffling motion to avoid slipping and falling on the huge balls of ice. The front windshield was completed marbled, every inch of our shining new car dimpled with deep depressions that equaled our own depression over what was going to happen when our mom and dad saw their brand new car! We were teenagers all and accustomed to that guilt that arose from a whole string of iniquities: dropping our mom’s favorite crystal bowl, staying out an hour past curfew, eating the last piece of pie. My sister backed the car out of the little turnoff she’d turned into hoping for some scant shelter from the hail and drove me and my friend the rest of the way to the registration in the mess hall, then she and her friend drove away. On the way home, they encountered a plague of grasshoppers that coated the windshield and they had to use bottles of Squirt to dissolve them from where they had become embedded into the marbled windshield; so this stickiness, dried in puddles on the hood of the car, added to the total devastation that greeted my dad’s eyes when his new “baby” was returned to him.

The feared recriminations never occurred. “Accidents happen. It wasn’t your fault,” said my dad. “I never really liked that color of green anyway,” said my mom. When my folks came to pick me up at camp, it was in a brand new rose-colored Pontiac Bonneville with a cream-colored top—the most beautiful car we ever owned. We met with no disasters on the way home, and four years later, it was the car I drove off to college six hundred miles away. My parents’ newest brand new car was a beige Buick that possessed none of the charm of the car now relegated to me, but did possess several new electronic features that I’m sure, for my dad, compensated completely.

The Prompt: You’re at the beach with some friends and/or family, enjoying the sun, nibbling on some watermelon. All of a sudden, within seconds, the weather shifts and hail starts descending form the sky. Write a post about what happens next.