Update Dec. 14, 2017: I’m very curious about why, three years after I posted this story about Agustin on my blog, I’ve suddenly had over 200 viewings of it in one day. If you’re reading this, would you please add a comment to tell me how you came to do so? Thanks, and thanks for viewing it!

The Prompt: Second-Hand Stories—What’s the best story someone else has recently told you (in person, preferably)? Share it with us, and feel free to embellish — that’s how good stories become great, after all.

I have been told many stories by Agustin, and some day I will share them with you, but I think they’ll have more power if you know more about the man, so today I want to tell you about him.

A number of years ago, a popular situation comedy in the U.S. was “Cheers,” a story about a Boston pub that became a home away from home for its regulars. Some of the lyrics from its enormously popular theme song were:

Making your way in the world today takes everything you’ve got.

Taking a break from all your worries, sure would help a lot. . . .

You wanna go where people know people are all the same,

You wanna go where everybody knows your name.

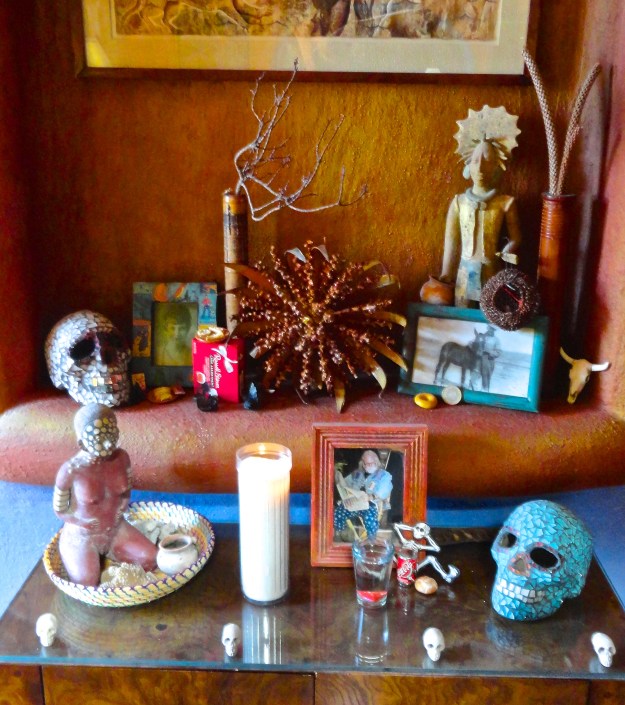

In San Juan Cosalá, Mexico, a pueblo of 6,000 on Lake Chapala, about an hour’s drive away from Guadalajara, that place is Agustin Vazquez’s restaurant, Viva Mexico. It is a warm, art-filled social center for the community that in my opinion also happens to serve the best food lakeside. Here as in the rest of his life, Agustin functions as half scholar, half artist, surveying other restaurants, cookbooks, websites and even literature such as Like Water for Chocolate for recipes that will enable him to bring to life again Mexico’s rich culinary history.

Quail in rose petal sauce is one such recipe which joins other special menu offerings such as fish fillets cooked in banana leaves with fresh herbs, chiles en nogada, pork shank, and ribs simmered in Agustin’s homemade sauce. Other traditional favorites are pozole (a rich pork and hominy stew) and molcajetes (beef, chicken or shrimp with sweet green peppers, onions, panela and other cheeses with a red or green sauce, cooked in a traditional stone receptacle). My favorite is a molcajete of chicken breast cooked in green sauce. Mmmmmmm. No one I’ve ever recommended it to has been disappointed, and I recommend it to everyone I see who is about to order.

More artistry is displayed in the presentation. Vegetables are fanned in flower shapes, organic lettuce supports the freshest tomato slices, and the entire plate becomes an artistic pleasure that makes one pause a moment to survey the plate before succumbing to the wonderful odors that presage delightful tastes and textures to be experienced.

Chiles en Nogada is a popular item on the menu.

Chiles en Nogada is a popular item on the menu.

A lifelong local resident who has his community and its people in his heart, Agustin is so busy that it is hard to imagine how he fits all of his obligations into one day, for his creation of one of the most popular restaurants in the area is just one small part of his life. He also helps to direct a charitable food operation that now feeds 100 families in his home village, personally purchasing the food and for years, delivering it to each family once a week. (Now the families come to receive their weekly ration from a new region of his restaurant that serves as a storage space and dispensa for Operation Feed.) Since he joined the program a few years ago, his skill in bargaining has allowed them to double the number of families who are helped by the program. He does not allow them to reimburse him for his gas or his time.

With his knowledge of the village, Agustin has cut the time for weekly food deliveries in half in the year since he has been doing the driving.

With his knowledge of the village, Agustin has cut the time for weekly food deliveries in half in the year since he has been doing the driving.

I first met Agustin in 2002 when I became involved with a group of local Mexican artists. Agustin, who at the time was working as a real estate agent and contractor, had long been their patrón (sponsor) and so when I approached them about helping to stage a children’s art experience where they would paint pictures on the theme of cleaning up the lakeside and their village, Agustin immediately became a major supporter of the project, helping to buy backpacks and school supplies for the prizes. When we staged a fundraising concert to send a young opera singer to the U.S., Agustin fed us all afterwards in what was then his Aunt Lupita’s pozole restaurant. At the time, it was dirt-floored, the simple kitchen was open to the air and parts of the restaurant were without a ceiling.

Agustin greets Isidro Xilonzochitl and other artists and friends who are regulars at Viva Mexico.

Agustin greets Isidro Xilonzochitl and other artists and friends who are regulars at Viva Mexico.

Now, ten years later, Agustin has added a beautiful stone floor, screened in the kitchen, added ceiling fans, colorful tablecloths and equipale chairs, purchased all new appliances and kitchen equipment, new bathrooms and a bar where local artists continue to meet most nights. If they are a bit short of money to pay for meals, it is fairly certain that they’ll be served a meal anyway. The walls reflect his support of local artists. Floor to ceiling on all sides, they are covered with their framed paintings, except for the east wall, which is entirely covered by a mural by Isidro Xilonzochitl. It depicts San Juan Cosalá as it was hundreds of years ago. “These guys—these artists and writers and musicians—have to be supported,” Agustin told me recently, “They are part of our community, as you, who live here also, are part of it.”

That statement forms the crux of the magic of a place like Agustin’s. It really is the place that binds us all—Mexican and expats—together. This first started to happen on September 12 of 2007, when weeks of rain were followed by a tromba (waterspout) that dumped water into the hills above the Raquet Club and the town, causing a tremendous downrush of water that brought boulders, dirt and everything in its path down the mountainside and into the town. Walls, buildings and roads gave way to the avalanche of water and rock, leaving much of the town devastated.

Agustin, who had recently purchased his aunt’s restaurant, stepped immediately into the fray, feeding the thousand or so displaced residents and relief workers three meals a day. Originally paying for the food out of his own pocket, he was eventually given food and aid by other residents, both Anglo and Mexican; and this is how the Mexican and Anglo communities were given a chance to mingle and get to know each other on a more intimate level. When I volunteered, Agustin first gave me a broom to sweep the dirt floor. By the end of the week, I was stirring huge pots of beef and waiting on tables as his restaurant filled three times a day.

The work was exhausting as Agustin and eventually, 25 volunteers, most of them family members, worked to provide three meals a day. By the end of ten days, this amounted to over 3,000 meals! By the time he had persuaded local politicians to take over this task, in addition to losing out on almost two weeks of income, Agustin was so in debt for supplies he had bought out of his own pocket that for two months, he questioned his ability to reopen the restaurant. Most of his knives, forks and salt and pepper shakers had been thoughtlessly carried away with carry-out meals. Teary-eyed, Agustin told me about local neighbors, poor themselves, who heard of his plight and offered him hands full of change to try to help, but in the end, he was still $75,000 pesos in debt.

With three sons and a wife to support, Agustin could not afford to take more of a break than was absolutely necessary, so mustering his courage, he somehow found the means to again open the restaurant which four years later has become the heart of the community.

Any night of the week that you venture into Viva Mexico, you are likely to encounter one of these “regulars.”

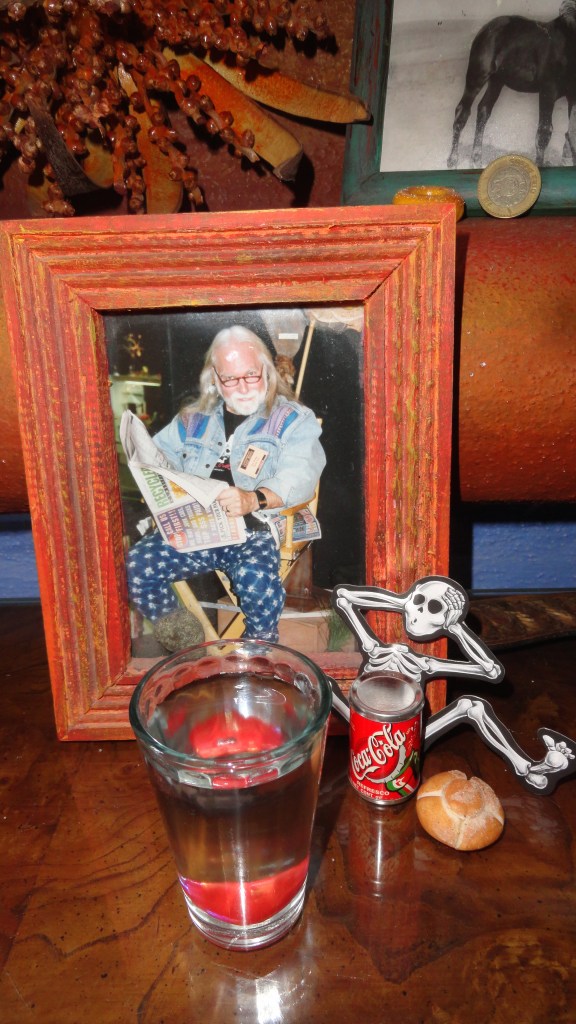

What factors go together to create these great qualities of entrepreneurism, courage, generosity and artistic sensibility in a man? Knowing a bit more about Agustin’s history might give us a clue. When he was born in San Juan Cosalá in 1966, the midwife told Agustin’s mother that this child was different and special, that he would bring luck to his family and all around him. When I asked Agustin what quality the midwife had noticed, he did not know, but later when we talked again, I asked him if he had been born with a caul over his head, as this is the traditional sign world-wide that a child is destined to greater things. When I described what this meant, Agustin nodded his head in agreement. This is how the midwife had described it, but he had never known the term for it.

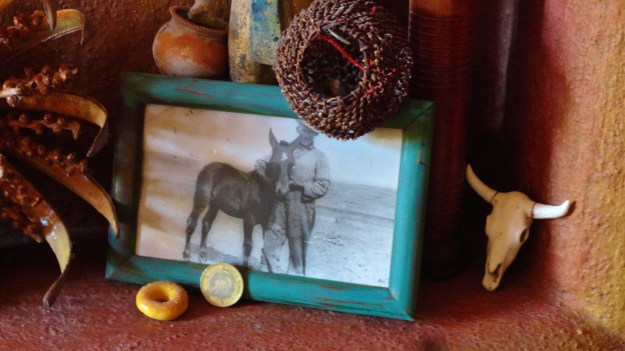

When Agustin was born, his father went to the United States to find work to support his family. At that time, Agustin was the fourth child but the first son born into a family that would eventually grow to five brothers, five sisters. Agustin himself began work at the age of six, cutting firewood or helping his grandpa with his fisherman’s nets after school. “My mother, she always pushed us to go to school,” said Agustin. “She could not read or write herself, but she was always encouraging me to look for another way to live. ‘I don’t want you to be like me,’ she said. Now I say the same thing to my sons.”

“I was a troublemaker in secondaria,” Agustin confessed to me, “because I always questioned the priest, wanting to know more.” Agustin credits Padre Adalberto Macias with changing the town through education. “He didn’t want me there, though, because all those questions were a disruption,” admits Agustin. Ironically, Agustin is now the man who drives to the Abastos (wholesale market) in Guadalajara each month to procure food and deliver it to Casa de Ninos y Jovenes, the residential school for disadvantaged youth run by Padre Adalberto.

In July of 1978, at the age of twelve, Agustin went north to the U.S. for the first time. His father put him in school in Lompoc, California for three or four months, but as one of only four Mexicans in the school, he was not treated well and he begged to be sent back to Mexico. Sadly, although he did manage to complete secondaria (tenth grade), there was no money to send him to preparatorio. Instead, at the age of 14, he quit school to blast rock at the Piedra Barrenada, the stone cliff north of the fish restaurants on the carretera (highway) east of San Juan Cosalá. “On Saturday and Sunday, I worked as a waiter,” Agustin told me.

When Agustin accepted his first job as a waiter, did he ever dream that one day he would be serving customers in his own restaurant, wearing a designer chef’s coat that was the gift of a customer?

When Agustin accepted his first job as a waiter, did he ever dream that one day he would be serving customers in his own restaurant, wearing a designer chef’s coat that was the gift of a customer?

“I worked many jobs. I cut chayote plants and corn with my family. For one year I was a carpenter with my cousin. When a company came to export chayote to the United States, they made me manager at the age of 15, even though I was the youngest. I don’t know why. Next, I was a waiter at the balneario (hot mineral water spa) until I went to the states with my brother in 1984.”

It was his mother who had intended to go north to find his father, whom they had not seen for three years. She had heard rumors that he was very ill and living in Tijuana, but how could she leave with so many children to cook for, she asked, and begged him to go in her place. He lived for one month in the streets of Tijuana, looking for his father. When he found him, his father was in a hospital, having just undergone surgery. Once he recovered, they had no money to return home, so they went to the U.S. where this time, Agustin worked in the fields with his father for one year. “Cities on the borderline are horrible,” he told me. “They are so sad. Many people from different countries with no money to leave. So sad.” After one year of working in the states, he came back to Mexico to work in construction.

He went back one more time to the States, to get his ailing father so he could die in Mexico. When his father died in 1989, as the oldest son, Agustin inherited responsibility for the family he had been helping to support for most of his life. “My father was a generous man,” Agustin told me, “who would give his shirt if people liked it. When I was a young boy, my uncle, who remained in San Juan, had a pool hall. It was a long time before I knew that my father had given him the pool tables, and that the nets my grandfather used as a fisherman were actually my father’s nets. He was a nice man, my father, but he had to go to the states to support his family. He went to the states when I was born and worked there until I was twenty years old, when he came home to die.”

In 1990, Agustin married Antonia, a local beauty queen. “I saw her at a dance,” he said, and chuckled guiltily as he added, “She was with my friend, but when I saw her, I just had to ask her to dance, and so I took her away from him. My mother didn’t want me to get married, wanted me to wait. I was already feeding ten people in my family, but I wanted to get married, and so I did.

Twenty-two years later, Antonia and Agustin share cooking duties in their newly refurbished kitchen.

Twenty-two years later, Antonia and Agustin share cooking duties in their newly refurbished kitchen.

I was intrigued over how a young man with a wife and ten other dependents was ever able to become the self-educated, well-read community-minded restaurateur that Agustin is. “How did you ever manage to get where you are today?” I asked, and Agustin, a natural-born storyteller, pulled up a chair to the table where I sat over my molcajete and resumed his tale.

“I got a job at a restaurant in Ajijic that was run by a couple from San Francisco. They had three restaurants: in Los Cabos, Puerto Vallarta and here. The woman was very tough, but nice, and I learned a lot from her. For one thing, I learned to focus. Four people together couldn’t compare to her chopping. While I was there, they taught me how to cook and to flambé. They helped me to be in contact with people. First I replaced the chief of waiters when he was gone, and after that I was the replacement for the bartender, waiter and cook. At that place I learned everything, but after one year, I had to quit. The cold and hot probably hurt my hands, because I started to get their kind of bones–the kind that grow (arthritis.)”

“When I went to apply for a job at Mama Chuy (a resort hotel near San Juan Cosalá) my wife was pregnant with our first son. I had to have a job, so I feigned experience. When they asked me if I knew English, I said yes. When they asked me how old I was, I said 28 or 29, but I was really 23. Everything they asked me, I said I knew how to do—except for maintaining the pools. ‘No, I said, but I can learn.’ When they asked me how much I wanted to be paid, I said, ‘Whatever you want to pay me,’ and I was hired on probation.”

“I worked there for five years and learned to speak English. I learned a lot at Mama Chuy’s. My first day, a guy from Massachusetts who was a guest there asked me if I wanted to learn English. When I said okay, he told me to be there tomorrow at six. That first day, he gave me the book Aztec by Gary Jennings and told me to read 20 or 30 pages. It was in Spanish, and that night I told my wife that for me it was an insult for him to give me this kind of book. But my wife told me to do what he told me.”

“When I saw him the next day, he asked if I had read the book and I said yes, but when he questioned me, he knew I hadn’t. Then he explained why he gave me the book. ‘The first thing you have to know is who you are,’ he said, ‘This book will teach you your own history.’ That was when I learned that you should never say ‘can’t.’ What you want, you have to go for. From that man, I learned everyday English. All the people at Mama Chuy helped me. In the five years I was there, I learned so many things. That man was a snowbird who came back every year and he taught me so many things. We became good friends. He 88 years old now…and in the states with Alzheimer’s.”

“During this time and afterwards, I taught English to 400 to 500 people from San Juan: gardeners, maids, taxi drivers, and students. This made me feel okay. I taught them for free or for one peso per class to buy diapers for my sons. Afterwards, I went to one or two schools to teach as well.

Three generations work together at Viva Mexico: Agustin, his Tia Lupita and his sons.

Three generations work together at Viva Mexico: Agustin, his Tia Lupita and his sons.

In the years to come, Agustin expanded his already extensive resume. First he became a contractor. “The best guys in town work for me,” he told me. “Just 5 guys. I don’t need more. They have worked for me for 18 years, whenever I need them.” When I asked him how he obtained his contracting experience, he admitted that here, too, he was self-educated. “I knew it in my dreams how to do it,” he confided. I was reminded of my recent trip to see Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio near Scottsdale, Arizona, where I had discovered that the same was true of Wright, who never had any formal architectural training.

“Trains pass by on a regular basis and I jumped on every one to see where it would take me.” said Agustin, referring to his ability to seize any available chance to self-educate. “The train, it doesn’t stop. You have to jump, run a little bit and get into the train.”

Other years were spent as a real estate broker. When he first was hired to work at Laguna Real Estate, he had no car, so he bought one. It was very hard, he said, because most of the customers were American and Canadian, so they preferred to work with the American and Canadian agents. He took classes in English, which were hard—a different level of English than he had learned formerly. In the first week, he sold a house, but received no commission.

For the next six or seven months, he sold no other houses and was ready to quit. The owner of the agency persuaded him to finish out the week. He made many phone calls, and ended up selling $2 million dollars US in two weeks. He worked there for five years, then changed agencies to work with another Mexican broker. “We took the leftovers,” he said, “the houses that didn’t cost so much, that the other brokers didn’t want; and we ended up doing six to seven closings a month.”

“If someone comes and offers me something, I will learn. Life is simple. We complicate our lives by wanting to have our own way. Like a bull. If you let him go, you can follow where he wants to go and it is easy to hold onto the bull. But if you pull, it’s not easy.”

When I asked him what his goals are for his sons, he answered, “Goals. I know my son’s life is not my life. I know it is his life. My first son is almost finished with University and will be an agricultural engineer, the second is in technical school to be a pilot and will be safe. The third (who quit school last year to support his girlfriend and baby, but who intends to go back to school next year) needs a push. This restaurant is for me, not necessarily for them. They need to find their own way. The people who work for me, I always try to help them as well.”

Agustin, his Tia Lupita and other members of his staff display their usual smiles.

Agustin, his Tia Lupita and other members of his staff display their usual smiles.

“What is left in life for you?” I ask him, and he answers, “Travel. If I had only myself to worry about, I would travel. People who travel live twice in their minds. Instead, I read, for people who read travel in their minds. Outside of his three trips to the U.S., what traveling he has done is in Mexico—every state except Chihuahua, Veracruz or Chiapas.

I know from an American friend who has had much advice from Agustin about what books to read, that Agustin is widely and well-read. When I ask him his favorite authors, he says, “I’d have many of those. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Octavio Paz, Juan Rulfo? Why not?”

When Ninos y Jovenes asked him to take over the purchasing of food and supplies for their residence school for disadvantaged children, his answer was yes, and he added this monthly task to his weekly trips to Guadalajara to buy food for Operation Feed. When Earl Smithburg, the former director of Operation Feed, died, Agustin provided the buses to transport people to his funeral.

When I asked him to drive me into some of the areas worst hit by the tromba for a follow-up story two years later, the answer was yes. When I asked his construction company to repair my roof, the answer was yes, and I don’t believe I ever received a final bill. I’ve asked about this countless times, and he never quite remembers what the amount is that I owe him.

He has amazing skills: carpenter, mason, real estate broker, resort manager, construction design, construction manager, restaurateur and chef. In addition to this, he is an outstanding family man, father, neighbor and friend. It came as no surprise to me at all that when I asked him if he’d ever had his IQ tested that he said yes. With prodding, I got him to confess that his IQ was 144—genius level.

In closing, I’d like to quote just a few of the statements that people made when I asked them their impressions of Agustin:

“Agustin consistently puts his personal needs behind the needs of others. He always thinks of others first when making decisions that will impact those around him.”

“Agustin recommended this incredible reading list for me. He is a self-taught scholar. He was a big reason why I stayed in Mexico. He has a heart that includes absolutely everyone.”

Agustin takes time out to talk with one of his regulars; and yes, they were talking about books.

Agustin takes time out to talk with one of his regulars; and yes, they were talking about books.

“He is the most unselfish man you will ever meet. He will give of himself by whatever means he has without thinking about the personal sacrifices that giving will cause.”

“He is a very trusting individual. If you pledge trust in return, you will enjoy a level of personal friendship that is truly without borders.”

“He is probably one of the last breeds of good old Mexican folk who grabs on to the land and to the culture of a bleeding patria (native land).”

“Humble and slow like an old dog who has been left the hard task of looking out to all those who depend on him and think of him as the ultimate guardian.”

“An absolute perfect host. He greets each person in his restaurant. If he is cooking at the time, he will wait until you are eating or afterwards, and then come up to your table, stand and talk for awhile, or if it’s a slow night, pull up a chair and talk to you.

“Multi-talented, really smart, Renaissance man. Genuinely cares about people. No haughtiness or pretense.”

“He has gotten to where he is by being absolutely nonpolitical. Everything he does, he does out of the goodness of his own heart, without a thought of his own gain. The help he furnished during the landslide was not for political reasons or anything other than that’s the kind of guy he is.”

“Agustin is an artist at work. He goes to the food sellers and warehouses for the charities he buys food for and he beats them down so badly on the prices that they aren’t making a whole lot of money.”

Energetic, generous, personable, devoted father, teacher, philanthropist, self-taught pillar of his family and community, a man with a heart of gold who goes out of his way to help others, Agustin Vasquez Calvario is a living testament to the truth that one person can make a difference.

(Viva Mexico is located two blocks west of the San Juan Cosalá Plaza at Porfirio Diaz #92. Call 387-761-1058 for directions or reservations.)

Judy’s note: This article was written a few years ago for an online magazine that is no more. In the years since then, Agustin has created a huge gourmet kitchen and doubled the size of his restaurant. The same artist who painted the mural inside has covered the outside of the restaurant with a huge mural that depicts the inside of the restaurant with every table filled with Agustin’s regular customers depicted. I’m at a table in the front row with my best friends around me. Sadly, I am the only one who still lives in Mexico.

Agustin has had many health challenges that have forced him to slow down and allow others to share some of the responsibilities he has always assumed. Although he has more helpers, new projects continue. He teaches English to Mexican adults and children, a children’s chorus now meets in the new half of his restaurant that only opens on weekends. A children’s orchestra has been started with instruments provided by solicitation of locals supportive of Agustin’s continuing schemes to give the youth of San Juan Cosala something to do more interesting than drugs and alcohol.

San Juan Cosala Children’s Choir. That’s Agustin’s granddaughter with the pink hair ribbon!

San Juan Cosala Children’s Choir. That’s Agustin’s granddaughter with the pink hair ribbon!

Twice a year, clothes are handed out here to the pueblo’s poorest and every week, food is dispensed to the 100 poorest families. Meat, vegetables and fruit have been added to the rations which formerly included only dry foodstuffs and oil. Things change and change as things do, but one thing that never changes is that Viva Mexico remains the heart of the community: both expat and Mexican.

Changes continue as the real Agustin, customers and friends all seem to be supervising the installation of new pavers that replace the former cobblestones of the road leading from the plaza to Viva Mexico.

Changes continue as the real Agustin, customers and friends all seem to be supervising the installation of new pavers that replace the former cobblestones of the road leading from the plaza to Viva Mexico.

UPDATE NOV. 29, 2016: We celebrated Agustin’s 50th birthday at Viva Mexico last night. See the story and photos in a new post HERE.