My Father in Me

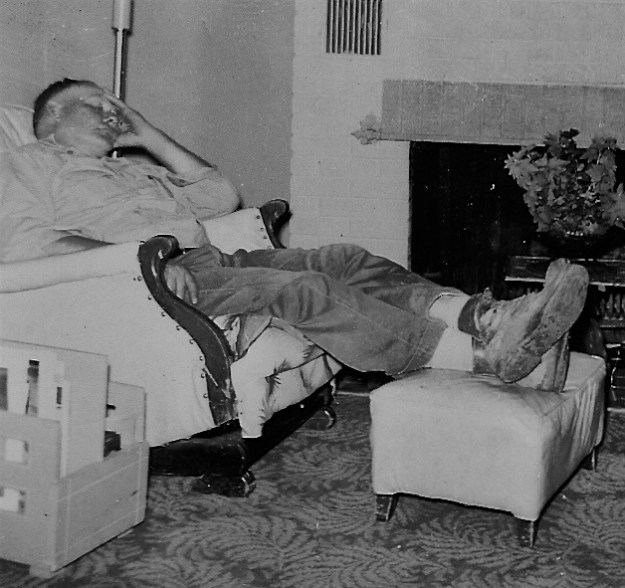

After those first two dreams, you never returned again, Dad. So now, more than 50 years after your death, I am instead looking for you within myself. I find you every time I retell an often-told tale adding embellishments as you did, or in my obsession with other people’s babies and that yearning to hold every one I see. I remember your holding the babies of tourists in Mack’s Cafe or Ferns “so their folks could finish their meals.” You loved the tiny ones most. As you explained it, “I like them mewling and puking in my arms!”

I recall all the abandoned baby animals you brought into our lives: a mole, a magpie, numerous baby rabbits, once a puppy held up in a cattle sales ring and tossed up to you in the third row, tiny yellow kittens and the best of all–Zippy, the tiny raccoon found in its nest after hunters killed its mother.

So it is you I see in me as I remember the wild cat from the redwoods shyly watching, then lured by food, who moved into my jewelry studio and gave birth, leaving us with three tiny blue Burmese kittens. And I count on my fingers eleven different puppies and six kittens adopted in the past 25 years since moving to Mexico–found in the street, by the lake, dumped in a cardboard box beside my garage. Is it you, father, delivering these tiny lost ones to me, knowing the you in me that has as much need of them as they have of me?

It was my father

guiding the wild cat to me,

three kittens within.

Click on photos to enlarge and read captions.

For dVerse Poets