He handed it to me without ceremony—a small leather bag, awl-punched and stitched together by hand. Its flap was held together by a clasp made from a two fishing line sinkers and a piece of woven wax linen. I unwound the wax linen and found inside a tiny wooden heart with his initials on one side, mine on the other. A small hole in the heart had a braided cord of wax linen strung through that was attached to the bag so that the heart could not be lost. He had woven more waxed linen into a neck cord. I was 39 years old when he gave me that incredible thing I never thought I would receive: his heart—as much of it as he could give. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Essays

Agustin’s Story

Update Dec. 14, 2017: I’m very curious about why, three years after I posted this story about Agustin on my blog, I’ve suddenly had over 200 viewings of it in one day. If you’re reading this, would you please add a comment to tell me how you came to do so? Thanks, and thanks for viewing it!

The Prompt: Second-Hand Stories—What’s the best story someone else has recently told you (in person, preferably)? Share it with us, and feel free to embellish — that’s how good stories become great, after all.

Agustin Vazquez Calvario: Renaissance Man and Good Samaritan of San Juan Cosalá

I have been told many stories by Agustin, and some day I will share them with you, but I think they’ll have more power if you know more about the man, so today I want to tell you about him.

A number of years ago, a popular situation comedy in the U.S. was “Cheers,” a story about a Boston pub that became a home away from home for its regulars. Some of the lyrics from its enormously popular theme song were:

Making your way in the world today takes everything you’ve got.

Taking a break from all your worries, sure would help a lot. . . .

You wanna go where people know people are all the same,

You wanna go where everybody knows your name.

In San Juan Cosalá, Mexico, a pueblo of 6,000 on Lake Chapala, about an hour’s drive away from Guadalajara, that place is Agustin Vazquez’s restaurant, Viva Mexico. It is a warm, art-filled social center for the community that in my opinion also happens to serve the best food lakeside. Here as in the rest of his life, Agustin functions as half scholar, half artist, surveying other restaurants, cookbooks, websites and even literature such as Like Water for Chocolate for recipes that will enable him to bring to life again Mexico’s rich culinary history.

Quail in rose petal sauce is one such recipe which joins other special menu offerings such as fish fillets cooked in banana leaves with fresh herbs, chiles en nogada, pork shank, and ribs simmered in Agustin’s homemade sauce. Other traditional favorites are pozole (a rich pork and hominy stew) and molcajetes (beef, chicken or shrimp with sweet green peppers, onions, panela and other cheeses with a red or green sauce, cooked in a traditional stone receptacle). My favorite is a molcajete of chicken breast cooked in green sauce. Mmmmmmm. No one I’ve ever recommended it to has been disappointed, and I recommend it to everyone I see who is about to order.

More artistry is displayed in the presentation. Vegetables are fanned in flower shapes, organic lettuce supports the freshest tomato slices, and the entire plate becomes an artistic pleasure that makes one pause a moment to survey the plate before succumbing to the wonderful odors that presage delightful tastes and textures to be experienced.

Chiles en Nogada is a popular item on the menu.

Chiles en Nogada is a popular item on the menu.

A lifelong local resident who has his community and its people in his heart, Agustin is so busy that it is hard to imagine how he fits all of his obligations into one day, for his creation of one of the most popular restaurants in the area is just one small part of his life. He also helps to direct a charitable food operation that now feeds 100 families in his home village, personally purchasing the food and for years, delivering it to each family once a week. (Now the families come to receive their weekly ration from a new region of his restaurant that serves as a storage space and dispensa for Operation Feed.) Since he joined the program a few years ago, his skill in bargaining has allowed them to double the number of families who are helped by the program. He does not allow them to reimburse him for his gas or his time.

With his knowledge of the village, Agustin has cut the time for weekly food deliveries in half in the year since he has been doing the driving.

With his knowledge of the village, Agustin has cut the time for weekly food deliveries in half in the year since he has been doing the driving.

I first met Agustin in 2002 when I became involved with a group of local Mexican artists. Agustin, who at the time was working as a real estate agent and contractor, had long been their patrón (sponsor) and so when I approached them about helping to stage a children’s art experience where they would paint pictures on the theme of cleaning up the lakeside and their village, Agustin immediately became a major supporter of the project, helping to buy backpacks and school supplies for the prizes. When we staged a fundraising concert to send a young opera singer to the U.S., Agustin fed us all afterwards in what was then his Aunt Lupita’s pozole restaurant. At the time, it was dirt-floored, the simple kitchen was open to the air and parts of the restaurant were without a ceiling.

Agustin greets Isidro Xilonzochitl and other artists and friends who are regulars at Viva Mexico.

Agustin greets Isidro Xilonzochitl and other artists and friends who are regulars at Viva Mexico.

Now, ten years later, Agustin has added a beautiful stone floor, screened in the kitchen, added ceiling fans, colorful tablecloths and equipale chairs, purchased all new appliances and kitchen equipment, new bathrooms and a bar where local artists continue to meet most nights. If they are a bit short of money to pay for meals, it is fairly certain that they’ll be served a meal anyway. The walls reflect his support of local artists. Floor to ceiling on all sides, they are covered with their framed paintings, except for the east wall, which is entirely covered by a mural by Isidro Xilonzochitl. It depicts San Juan Cosalá as it was hundreds of years ago. “These guys—these artists and writers and musicians—have to be supported,” Agustin told me recently, “They are part of our community, as you, who live here also, are part of it.”

That statement forms the crux of the magic of a place like Agustin’s. It really is the place that binds us all—Mexican and expats—together. This first started to happen on September 12 of 2007, when weeks of rain were followed by a tromba (waterspout) that dumped water into the hills above the Raquet Club and the town, causing a tremendous downrush of water that brought boulders, dirt and everything in its path down the mountainside and into the town. Walls, buildings and roads gave way to the avalanche of water and rock, leaving much of the town devastated.

Agustin, who had recently purchased his aunt’s restaurant, stepped immediately into the fray, feeding the thousand or so displaced residents and relief workers three meals a day. Originally paying for the food out of his own pocket, he was eventually given food and aid by other residents, both Anglo and Mexican; and this is how the Mexican and Anglo communities were given a chance to mingle and get to know each other on a more intimate level. When I volunteered, Agustin first gave me a broom to sweep the dirt floor. By the end of the week, I was stirring huge pots of beef and waiting on tables as his restaurant filled three times a day.

The work was exhausting as Agustin and eventually, 25 volunteers, most of them family members, worked to provide three meals a day. By the end of ten days, this amounted to over 3,000 meals! By the time he had persuaded local politicians to take over this task, in addition to losing out on almost two weeks of income, Agustin was so in debt for supplies he had bought out of his own pocket that for two months, he questioned his ability to reopen the restaurant. Most of his knives, forks and salt and pepper shakers had been thoughtlessly carried away with carry-out meals. Teary-eyed, Agustin told me about local neighbors, poor themselves, who heard of his plight and offered him hands full of change to try to help, but in the end, he was still $75,000 pesos in debt.

With three sons and a wife to support, Agustin could not afford to take more of a break than was absolutely necessary, so mustering his courage, he somehow found the means to again open the restaurant which four years later has become the heart of the community.

Any night of the week that you venture into Viva Mexico, you are likely to encounter one of these “regulars.”

What factors go together to create these great qualities of entrepreneurism, courage, generosity and artistic sensibility in a man? Knowing a bit more about Agustin’s history might give us a clue. When he was born in San Juan Cosalá in 1966, the midwife told Agustin’s mother that this child was different and special, that he would bring luck to his family and all around him. When I asked Agustin what quality the midwife had noticed, he did not know, but later when we talked again, I asked him if he had been born with a caul over his head, as this is the traditional sign world-wide that a child is destined to greater things. When I described what this meant, Agustin nodded his head in agreement. This is how the midwife had described it, but he had never known the term for it.

When Agustin was born, his father went to the United States to find work to support his family. At that time, Agustin was the fourth child but the first son born into a family that would eventually grow to five brothers, five sisters. Agustin himself began work at the age of six, cutting firewood or helping his grandpa with his fisherman’s nets after school. “My mother, she always pushed us to go to school,” said Agustin. “She could not read or write herself, but she was always encouraging me to look for another way to live. ‘I don’t want you to be like me,’ she said. Now I say the same thing to my sons.”

“I was a troublemaker in secondaria,” Agustin confessed to me, “because I always questioned the priest, wanting to know more.” Agustin credits Padre Adalberto Macias with changing the town through education. “He didn’t want me there, though, because all those questions were a disruption,” admits Agustin. Ironically, Agustin is now the man who drives to the Abastos (wholesale market) in Guadalajara each month to procure food and deliver it to Casa de Ninos y Jovenes, the residential school for disadvantaged youth run by Padre Adalberto.

In July of 1978, at the age of twelve, Agustin went north to the U.S. for the first time. His father put him in school in Lompoc, California for three or four months, but as one of only four Mexicans in the school, he was not treated well and he begged to be sent back to Mexico. Sadly, although he did manage to complete secondaria (tenth grade), there was no money to send him to preparatorio. Instead, at the age of 14, he quit school to blast rock at the Piedra Barrenada, the stone cliff north of the fish restaurants on the carretera (highway) east of San Juan Cosalá. “On Saturday and Sunday, I worked as a waiter,” Agustin told me.

When Agustin accepted his first job as a waiter, did he ever dream that one day he would be serving customers in his own restaurant, wearing a designer chef’s coat that was the gift of a customer?

When Agustin accepted his first job as a waiter, did he ever dream that one day he would be serving customers in his own restaurant, wearing a designer chef’s coat that was the gift of a customer?

“I worked many jobs. I cut chayote plants and corn with my family. For one year I was a carpenter with my cousin. When a company came to export chayote to the United States, they made me manager at the age of 15, even though I was the youngest. I don’t know why. Next, I was a waiter at the balneario (hot mineral water spa) until I went to the states with my brother in 1984.”

It was his mother who had intended to go north to find his father, whom they had not seen for three years. She had heard rumors that he was very ill and living in Tijuana, but how could she leave with so many children to cook for, she asked, and begged him to go in her place. He lived for one month in the streets of Tijuana, looking for his father. When he found him, his father was in a hospital, having just undergone surgery. Once he recovered, they had no money to return home, so they went to the U.S. where this time, Agustin worked in the fields with his father for one year. “Cities on the borderline are horrible,” he told me. “They are so sad. Many people from different countries with no money to leave. So sad.” After one year of working in the states, he came back to Mexico to work in construction.

He went back one more time to the States, to get his ailing father so he could die in Mexico. When his father died in 1989, as the oldest son, Agustin inherited responsibility for the family he had been helping to support for most of his life. “My father was a generous man,” Agustin told me, “who would give his shirt if people liked it. When I was a young boy, my uncle, who remained in San Juan, had a pool hall. It was a long time before I knew that my father had given him the pool tables, and that the nets my grandfather used as a fisherman were actually my father’s nets. He was a nice man, my father, but he had to go to the states to support his family. He went to the states when I was born and worked there until I was twenty years old, when he came home to die.”

In 1990, Agustin married Antonia, a local beauty queen. “I saw her at a dance,” he said, and chuckled guiltily as he added, “She was with my friend, but when I saw her, I just had to ask her to dance, and so I took her away from him. My mother didn’t want me to get married, wanted me to wait. I was already feeding ten people in my family, but I wanted to get married, and so I did.

Twenty-two years later, Antonia and Agustin share cooking duties in their newly refurbished kitchen.

Twenty-two years later, Antonia and Agustin share cooking duties in their newly refurbished kitchen.

I was intrigued over how a young man with a wife and ten other dependents was ever able to become the self-educated, well-read community-minded restaurateur that Agustin is. “How did you ever manage to get where you are today?” I asked, and Agustin, a natural-born storyteller, pulled up a chair to the table where I sat over my molcajete and resumed his tale.

“I got a job at a restaurant in Ajijic that was run by a couple from San Francisco. They had three restaurants: in Los Cabos, Puerto Vallarta and here. The woman was very tough, but nice, and I learned a lot from her. For one thing, I learned to focus. Four people together couldn’t compare to her chopping. While I was there, they taught me how to cook and to flambé. They helped me to be in contact with people. First I replaced the chief of waiters when he was gone, and after that I was the replacement for the bartender, waiter and cook. At that place I learned everything, but after one year, I had to quit. The cold and hot probably hurt my hands, because I started to get their kind of bones–the kind that grow (arthritis.)”

“When I went to apply for a job at Mama Chuy (a resort hotel near San Juan Cosalá) my wife was pregnant with our first son. I had to have a job, so I feigned experience. When they asked me if I knew English, I said yes. When they asked me how old I was, I said 28 or 29, but I was really 23. Everything they asked me, I said I knew how to do—except for maintaining the pools. ‘No, I said, but I can learn.’ When they asked me how much I wanted to be paid, I said, ‘Whatever you want to pay me,’ and I was hired on probation.”

“I worked there for five years and learned to speak English. I learned a lot at Mama Chuy’s. My first day, a guy from Massachusetts who was a guest there asked me if I wanted to learn English. When I said okay, he told me to be there tomorrow at six. That first day, he gave me the book Aztec by Gary Jennings and told me to read 20 or 30 pages. It was in Spanish, and that night I told my wife that for me it was an insult for him to give me this kind of book. But my wife told me to do what he told me.”

“When I saw him the next day, he asked if I had read the book and I said yes, but when he questioned me, he knew I hadn’t. Then he explained why he gave me the book. ‘The first thing you have to know is who you are,’ he said, ‘This book will teach you your own history.’ That was when I learned that you should never say ‘can’t.’ What you want, you have to go for. From that man, I learned everyday English. All the people at Mama Chuy helped me. In the five years I was there, I learned so many things. That man was a snowbird who came back every year and he taught me so many things. We became good friends. He 88 years old now…and in the states with Alzheimer’s.”

“During this time and afterwards, I taught English to 400 to 500 people from San Juan: gardeners, maids, taxi drivers, and students. This made me feel okay. I taught them for free or for one peso per class to buy diapers for my sons. Afterwards, I went to one or two schools to teach as well.

Three generations work together at Viva Mexico: Agustin, his Tia Lupita and his sons.

Three generations work together at Viva Mexico: Agustin, his Tia Lupita and his sons.

In the years to come, Agustin expanded his already extensive resume. First he became a contractor. “The best guys in town work for me,” he told me. “Just 5 guys. I don’t need more. They have worked for me for 18 years, whenever I need them.” When I asked him how he obtained his contracting experience, he admitted that here, too, he was self-educated. “I knew it in my dreams how to do it,” he confided. I was reminded of my recent trip to see Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio near Scottsdale, Arizona, where I had discovered that the same was true of Wright, who never had any formal architectural training.

“Trains pass by on a regular basis and I jumped on every one to see where it would take me.” said Agustin, referring to his ability to seize any available chance to self-educate. “The train, it doesn’t stop. You have to jump, run a little bit and get into the train.”

Other years were spent as a real estate broker. When he first was hired to work at Laguna Real Estate, he had no car, so he bought one. It was very hard, he said, because most of the customers were American and Canadian, so they preferred to work with the American and Canadian agents. He took classes in English, which were hard—a different level of English than he had learned formerly. In the first week, he sold a house, but received no commission.

For the next six or seven months, he sold no other houses and was ready to quit. The owner of the agency persuaded him to finish out the week. He made many phone calls, and ended up selling $2 million dollars US in two weeks. He worked there for five years, then changed agencies to work with another Mexican broker. “We took the leftovers,” he said, “the houses that didn’t cost so much, that the other brokers didn’t want; and we ended up doing six to seven closings a month.”

“If someone comes and offers me something, I will learn. Life is simple. We complicate our lives by wanting to have our own way. Like a bull. If you let him go, you can follow where he wants to go and it is easy to hold onto the bull. But if you pull, it’s not easy.”

When I asked him what his goals are for his sons, he answered, “Goals. I know my son’s life is not my life. I know it is his life. My first son is almost finished with University and will be an agricultural engineer, the second is in technical school to be a pilot and will be safe. The third (who quit school last year to support his girlfriend and baby, but who intends to go back to school next year) needs a push. This restaurant is for me, not necessarily for them. They need to find their own way. The people who work for me, I always try to help them as well.”

Agustin, his Tia Lupita and other members of his staff display their usual smiles.

Agustin, his Tia Lupita and other members of his staff display their usual smiles.

“What is left in life for you?” I ask him, and he answers, “Travel. If I had only myself to worry about, I would travel. People who travel live twice in their minds. Instead, I read, for people who read travel in their minds. Outside of his three trips to the U.S., what traveling he has done is in Mexico—every state except Chihuahua, Veracruz or Chiapas.

I know from an American friend who has had much advice from Agustin about what books to read, that Agustin is widely and well-read. When I ask him his favorite authors, he says, “I’d have many of those. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Octavio Paz, Juan Rulfo? Why not?”

When Ninos y Jovenes asked him to take over the purchasing of food and supplies for their residence school for disadvantaged children, his answer was yes, and he added this monthly task to his weekly trips to Guadalajara to buy food for Operation Feed. When Earl Smithburg, the former director of Operation Feed, died, Agustin provided the buses to transport people to his funeral.

When I asked him to drive me into some of the areas worst hit by the tromba for a follow-up story two years later, the answer was yes. When I asked his construction company to repair my roof, the answer was yes, and I don’t believe I ever received a final bill. I’ve asked about this countless times, and he never quite remembers what the amount is that I owe him.

He has amazing skills: carpenter, mason, real estate broker, resort manager, construction design, construction manager, restaurateur and chef. In addition to this, he is an outstanding family man, father, neighbor and friend. It came as no surprise to me at all that when I asked him if he’d ever had his IQ tested that he said yes. With prodding, I got him to confess that his IQ was 144—genius level.

In closing, I’d like to quote just a few of the statements that people made when I asked them their impressions of Agustin:

“Agustin consistently puts his personal needs behind the needs of others. He always thinks of others first when making decisions that will impact those around him.”

“Agustin recommended this incredible reading list for me. He is a self-taught scholar. He was a big reason why I stayed in Mexico. He has a heart that includes absolutely everyone.”

Agustin takes time out to talk with one of his regulars; and yes, they were talking about books.

Agustin takes time out to talk with one of his regulars; and yes, they were talking about books.

“He is the most unselfish man you will ever meet. He will give of himself by whatever means he has without thinking about the personal sacrifices that giving will cause.”

“He is a very trusting individual. If you pledge trust in return, you will enjoy a level of personal friendship that is truly without borders.”

“He is probably one of the last breeds of good old Mexican folk who grabs on to the land and to the culture of a bleeding patria (native land).”

“Humble and slow like an old dog who has been left the hard task of looking out to all those who depend on him and think of him as the ultimate guardian.”

“An absolute perfect host. He greets each person in his restaurant. If he is cooking at the time, he will wait until you are eating or afterwards, and then come up to your table, stand and talk for awhile, or if it’s a slow night, pull up a chair and talk to you.

“Multi-talented, really smart, Renaissance man. Genuinely cares about people. No haughtiness or pretense.”

“He has gotten to where he is by being absolutely nonpolitical. Everything he does, he does out of the goodness of his own heart, without a thought of his own gain. The help he furnished during the landslide was not for political reasons or anything other than that’s the kind of guy he is.”

“Agustin is an artist at work. He goes to the food sellers and warehouses for the charities he buys food for and he beats them down so badly on the prices that they aren’t making a whole lot of money.”

Energetic, generous, personable, devoted father, teacher, philanthropist, self-taught pillar of his family and community, a man with a heart of gold who goes out of his way to help others, Agustin Vasquez Calvario is a living testament to the truth that one person can make a difference.

(Viva Mexico is located two blocks west of the San Juan Cosalá Plaza at Porfirio Diaz #92. Call 387-761-1058 for directions or reservations.)

Judy’s note: This article was written a few years ago for an online magazine that is no more. In the years since then, Agustin has created a huge gourmet kitchen and doubled the size of his restaurant. The same artist who painted the mural inside has covered the outside of the restaurant with a huge mural that depicts the inside of the restaurant with every table filled with Agustin’s regular customers depicted. I’m at a table in the front row with my best friends around me. Sadly, I am the only one who still lives in Mexico.

Agustin has had many health challenges that have forced him to slow down and allow others to share some of the responsibilities he has always assumed. Although he has more helpers, new projects continue. He teaches English to Mexican adults and children, a children’s chorus now meets in the new half of his restaurant that only opens on weekends. A children’s orchestra has been started with instruments provided by solicitation of locals supportive of Agustin’s continuing schemes to give the youth of San Juan Cosala something to do more interesting than drugs and alcohol.

San Juan Cosala Children’s Choir. That’s Agustin’s granddaughter with the pink hair ribbon!

San Juan Cosala Children’s Choir. That’s Agustin’s granddaughter with the pink hair ribbon!

Twice a year, clothes are handed out here to the pueblo’s poorest and every week, food is dispensed to the 100 poorest families. Meat, vegetables and fruit have been added to the rations which formerly included only dry foodstuffs and oil. Things change and change as things do, but one thing that never changes is that Viva Mexico remains the heart of the community: both expat and Mexican.

Changes continue as the real Agustin, customers and friends all seem to be supervising the installation of new pavers that replace the former cobblestones of the road leading from the plaza to Viva Mexico.

Changes continue as the real Agustin, customers and friends all seem to be supervising the installation of new pavers that replace the former cobblestones of the road leading from the plaza to Viva Mexico.

UPDATE NOV. 29, 2016: We celebrated Agustin’s 50th birthday at Viva Mexico last night. See the story and photos in a new post HERE.

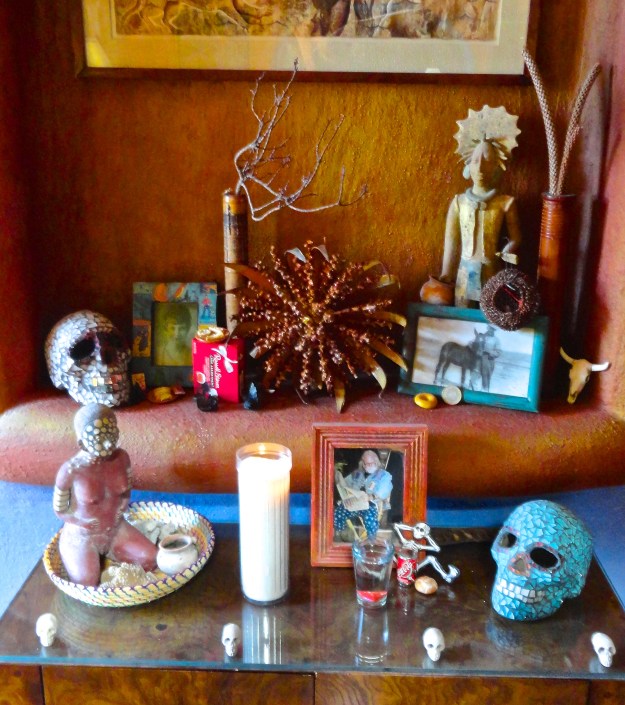

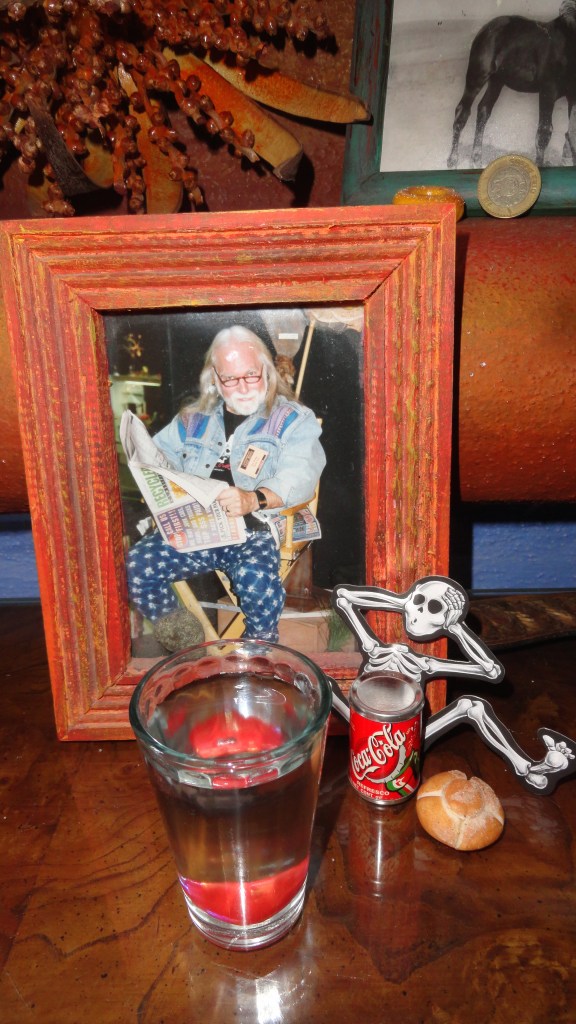

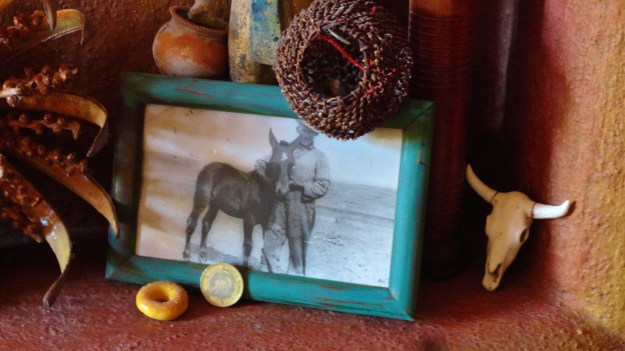

Dia de Los Muertos, 2014

Dia de los Muertos, 2014

This is this year’s minimalist altar for my departed: husband Bob, Mother Pat and Father Ben. I wasn’t going to do one. Then Yolanda (my housekeeper) told me about a friend who didn’t make a Dia de los Muertos altar for her mother who had recently died. This friend then went to see the elaborate offerings of her brothers and sisters, so she brought a rather poor specimen of a pumpkin and told them they could put that on her mother’s grave. That night she had a dream of walking through the graveyard. Every other grave was elaborately decorated with flowers and sweetly-scented candles and favorite foods of the departed: water, whiskey, tequila. When she got to her mother’s grave, there was no light and there were no offerings—only the one poor pumpkin. As she walked by, people shook their heads, and she left in shame. When she woke up, she went to her mother’s grave and took her fresh water, a candle, sweets, and all of the things her mother loved.

It worked. I assembled an altar. Yolanda looked at it and told another story about how the water and candle help to create a breeze that brings the scent of the favorite foods to the departed. I quickly added a candle and a small glass of water with an ice cube—as Bob did hate a lukewarm Coke! When the ice cube melted, I added a small red heart to take its place. If you look closely, you can see it in the bottom of the glass.

It was my mother’s tradition to tuck a small box of Russell Stover candy into each of our Xmas stockings. One Xmas, we opened them to find only wrappers in each one. Over the course of the weeks before Xmas, our mother had opened each one, unable to resist eating the chocolates. So precedent decreed that I eat hers. You’ll see the empty papers littering the space around the box. (Yolanda, ever-respectful of tradition, helped by eating one piece.)

Although my father raised black Angus and Hereford cattle, this is Mexico, after all, so I think he’d forgive the long horns. A donut and a 10 peso piece complete his offerings. Last year I put a small glass of milk with cornbread crushed in it—his favorite cocktail. But this year the ants have taken over our part of Mexico, so I didn’t dare.

Shell Game

The Prompt: In Retrospect—Yesterday you invented a new astrological sign. Today, write your own horoscope — for the past month (in other words, as if you’d written it October 1st).

Shell Game: Cancer the Crab Horoscope for October, 2014:

The hermit crab will come out of your shell during this month without the usual impulse of wanting to retreat back inside in response to the frustrations of a too-busy world. Variety is the spice of life, but too many things done often lead to none being done well. This month there will be a tendency to schedule too many activities and to become overextended. Vital matters will be overlooked as you attend to the matters of others. As you do even more than your usual amount of scurrying around, you should take care to schedule time for rest and relaxation lest a too-busy schedule cause your crabbiness to become more obvious than usual.

For the busy Cancerian, October is the month to do all those things neglected for too long such as wills and other legal matters. Time to clean out those garage shelves and to dip into boxes unopened for too many years and to sort and discard.

Time spent with an old friend might lead you to make faulty decisions regarding travel. This month it would be better to stay closer to home, lest you regret plans made hastily with too little research.

Creativity will be on the upswing as you deal with collaborations on many fronts and move to complete projects begun long ago and left unfinished for too long.

On the romantic front, semantic differences will be largely to blame for a misunderstanding with a loved one. The clarification of old issues again brought to light may cause pain as each struggles to see the world from the other’s vantage point. The forward-thinking Cancerian will remember that there is no gain without pain and take comfort from the fact that towards the end of the month, the growing pains accompanying this period of rapid growth will ease for both of you.

There is Always Music

There is Always Music

The music of Mexico is composed of a cacophony of sounds—all of them loud! Trumpets, drums, violins, guitars, tubas and trombones are backed up by fiesta revelers, insects, burros, cattle, roosters, fireworks, church bells, air brakes, stone drills and vendors driving the street with loudspeakers announcing gas, produce, knife-sharpening or bottled water for sale.

Living in Mexico is like living in a place where one or another of your neighbors celebrates a party every other day of the week. Patriotic holidays, weddings, saints days, baptisms, funerals, fifteenth birthdays—all are occasions for fiestas of often grand proportions; and although these parties do not always take place in your own neighborhood, the lake and mountains act as a sounding board which makes it sound as though they do.

Recently, it has become the style to set off fireworks from a boat positioned mid lake to celebrate nuptials. Then loud music and loudspeaker shouts proceed far into the night. Tonight as I got home a half hour before midnight, the music was so loud that it could have been coming from the house next door, but it was coming from a large hall on the carretera a half mile away. It was a wedding party I had seen the beginnings of earlier in the day, now grown into a full-scale bash.

The loudest celebrations are held on saints’ days or national holidays. These celebrations are frequent, as in addition to the usual holidays such as Dia de la Independencia and Aniversario del Revolución, each town has a ten-day celebration of the town’s patron saint. During one week-long celebration in the nearby town of Ajijic, it is rumored that 10,000 bottle rockets were set off, each of them launched into the air and exploding at the decibel level of a cherry bomb.

To demonstrate the frequency of such celebrations, take the six-day period of April 30 to May 5. The most famous Mexican holiday in the U.S. is Cinco del Mayo, but in Mexico, but in Mexico it is a celebration of minor importance. There are four other major holidays in the five days leading up to it, all of them more important. The week starts out on April 31 with El Dia del Nino, a celebration and parade for the day of the child, followed the next day by labor day—Dia del Trabajo—the day of the laborer. After a day’s vacation from holidays, there is Dia de Santa Cruz, followed two days later by Cinco de Mayo, the commemoration of the Battle of Pueblo. All of these celebrations bring with them the sounds of revelry: loud banda music, fireworks, guns fired into the air and the accompanying barks of protesting dogs and encouragement of human revelers.

In December, Christmas is preceded by the week-long commemoration of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which in my village is the occasion for hundreds of plant-decked altars to be set up along the streets in front of houses, garlands over the street and cobblestones strewn with fresh alfalfa. One day in early December, a neighbor came by to visit. Later, we went for a walk in the San Juan Cosala main plaza. The most beautiful feature of the square was a large faded portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe that stood near the church. Flowers and lights surrounded it in preparation for her saint’s day. Unfortunately, one of the strings of colored lights that swathed the portrait was a musical strand. In the fifteen minutes we took to traverse the square, we heard nasal computer-like renditions of, “I Wish You a Merry Christmas,” “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” and “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”

There is always music. Now the steady hum of the pump which recycles water from the jacuzzi to water the plants stops and I hear the steady whisk whisk whisk of the gardener’s broom on the stone patio. Outside hundreds of bees hum around the Virginia creeper that blankets the awning over the patio.

Birds furnish a counterpoint harmony to these domestic arias. In the few months that I have been living here, I believe I’ve heard whippoorwills, Baltimore orioles, grackles, and tanagers. I have heard the mysterious night call of a bird with a voice disguised as an interloper whispering, “Pssssst. Pssssst.” (I have since learned that this is probably an insect.) I have never seen either this bird or the bird whose call sounds like a squeegee being scraped against a chalkboard, but I did eventually see the ubiquitous insect called a rainbird (local name for a cicada) whose voices (by the thousands) proceed from a few seconds of castanet sounds to the buzz saw melody that fills the hills and trees around my house with their mating music in May and June .

In my first six months living lakeside, my solitude has been broken by few people other than my housekeeper, gardener, workers and repairmen who make daily pilgrimages to my house to correct problems at about the same rate as they create them. When now and then they switch off the loud competing blarings of their individual radios, I hear music in the noises of their industry as they administer to the house and grounds like neophytes to a high priestess. It is the house that is the god here, not me. I sit in another part of it making my own music on the keys of my laptop.

This morning, I awoke to the chink chink chink of the gardener’s shovel as he dug concrete chunks from the flowerbed beside my pool. He used neither of the new shovels I bought him, but instead the flat edged old shovel with the handle broken in half. I have stopped demanding or even suggesting that anyone do things the easy way. The squeegee sits dry in the storeroom along with the dried out sponge mop. Nearby are the damp rags and buckets are are actually used to wash the windows; and in the living room, I can hear the rhythmic slosh of Lourdes moving the string mop that is used so frequently that it rarely dries out.

On Monday, as Lourdes ironed in the spare room, I asked if she wished to listen to my Spanish/English tapes. If it is true that she will soon go to join relatives in the States, she should know some English. She nodded yes enthusiastically, but after one cycle, she removed the tape and switched to the radio. I could hear her singing along even two rooms away through two closed doors. She sang slightly off key, in a happy voice, unaware that anyone listened. In the afternoon, she ironed 30 garments, even though I had asked her to iron only three. As she ironed, she sang.

Every day I learn more about Mexico. On this day I have learned this. The pool man may be missing, there may be no water in the aljibe (cistern), and you can be sure that if you need hardware, the hardware store will be closed for comida (the afternoon meal). If you want to go to the restaurant you have passed twenty times, on the day you go it will be closed. There is a page-long list of things my house needs that I cannot find. But on this day, I learned of one thing that you can always find. In Mexico, there is always music.

–by Judy Dykstra-Brown

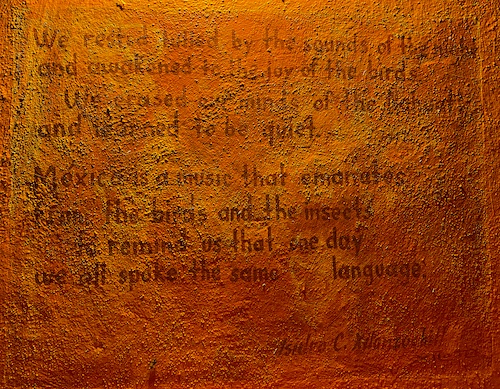

Twenty years ago when I moved to Mexico, I wrote the above piece for a local magazine and when the time came that I wanted a local artist, Isidro Xilonxochitl, to paint a mural on my outside wall, I asked him to use the themes from my essay.

He painted a wall covered by birds and insects, but also wrote a poem in Spanish that I translated into English. Wall damage made it necessary to paint over the mural years ago, but the poem is still painted on my wall. If you can’t make it out from the photo, I’ve rewritten it below. (Note: Nahuatl is a language of the Uto-Aztecan language family.)

We rested lulled by the sounds of the night

and awakened to the joy of the birds.

We erased our minds of the Nahuatl

and learned to be quiet.

Mexico is a music that emanates

from the birds and the insects

to remind us that one day

we all spoke the same language.

— Isidro C. Xilonsochitl

This post is for Sam, because he asked.

Too Much, Too Many

The Prompt: “Perhaps too much of everything is as bad as too little.” – Edna Ferber. Do you agree with this statement on excess?

Lately, I’ve taken to having panic attacks late at night as I’m trying to fall asleep. When I’m having one of these episodes, I suddenly feel as though I’m not going to be able to breathe. It’s not that I can’t breathe at the moment, but a feeling that I’m soon not going to be able to breathe. Sometimes it helps to use an inhaler, then to substitute one pillow for two and to lie on my back rather than my side, as I usually sleep; but more often than not, the only way I can stem the rising panic is to go outside in the fresh air and to sit for awhile, or walk.

This doesn’t happen every night, but it happens too often for comfort. I live alone, and although from time to time I miss company, these late night episodes are the only times when I fear being alone. Perhaps a vision of someday being old and vulnerable is what prompts them, but I know the reason why that fear is expressed as an inability to breathe is because of a TV show I watched over a year ago wherein a young boy was bound, blindfolded and buried alive as water slowly filled up the tank he was buried in, eventually drowning him after 24 hours of torture during which he was aware of his eventual fate. I can think of no more horrible death, and I would give a thousand dollars not to have seen that scene. I no longer watch the show but its damage has been done and it is that scene, along with an earlier scene where I was trapped underwater and came very close to drowning that fuel my conscious nightmares during this time.

In my daylight world, I have a similar fear of being buried under things. My main problems are tool, art supplies and papers—many of which are equally worthless to me. (Closets full of too-small or too-large clothes I just might shrink down to or grow into again, my husband’s stone-drilling tools that have resided in two large cupboards in my garage for 13 years and never used, my income tax returns and receipts that go back to 1964, a lifetime of letters and drawers and shelves of art supplies and collage items I’m fairly sure I’ll never use.) Yet, I have an irrational fear that the minute I rid myself of them, I will need them. I also have paintings stored in every closet as well as under a high rise bed I had made in my upstairs guest room—a bed with a drawer that holds 20 paintings—some by famous painters, some by myself. I would not hang my paintings, but also cannot throw them away or sell them. Nor can I throw away any of the probably 50,000 items that fill every shelf, drawer, bag, surface and hidden spot of my art studio. I make excuses for myself. I am a collage artist. I teach classes and I may need them to share. They have sentimental value.

My house is not messy (except for desktops and my studio) and there is generally a place for everything. It is clean, thanks to a three-times-a-week housecleaner. When company comes, I usually finally organize my desk, file the papers and cover those I don’t get filed with a beautiful scarf or sari, but I know there is a clutter hidden in a drawer or under a beautiful cover, and this disorganization chokes me as surely as my night panics.

My grandmother was a hoarder and so was my oldest sister. I tell myself I have this in control more than they did; but occasionally, when the piles on the built in desk that covers one wall in my bedroom spill over onto the chair, I start to fear that the family curse is taking me over. And in the dark, I can sense it growing nearer, its arms stretched out and its hands aching to encircle my neck and to choke me, shutting off my air slowly, over the years, leaving my middle sister (the uncluttered one) to finally do what I have not been able to do: to rid my house of too much, too many—the irony being that I will be the first object they will have to remove to enable her to do it!

Leftovers

When my father died forty years ago, it was in Arizona, where my parents had been spending their winters for the past ten years. They maintained houses in two places, returning to South Dakota for the summers. But after my father died, my mother never again entered that house in the town where I’d grown up.

Our family had scattered like fall leaves by then—my mother to Arizona, one sister to Iowa, another to Wyoming. Both the youngest and the only unmarried one, I had fallen the furthest from the family tree. I had just returned from Africa, and so it fell to me to drive to South Dakota to pack up the house and to decide which pieces of our old life I might choose to build my new life upon and to dispose of the rest.

My father’s accumulations were not ones to fill a house. There were whole barns and fields of him, but none that needed to be dealt with. All had been sold before and so what was to be sorted out was the house. In that house, the drapes and furniture and cushions and cupboards were mainly the remnants of my mother’s life: clothes and nicknacks, pots and pans, spice racks full of those limited flavors known to the family of my youth—salt and pepper and spices necessary for recipes no more exotic than pumpkin pies, sage dressings and beef stews.

Packing up my father was as easy as putting the few work clothes he’d left in South Dakota into boxes and driving them to the dump. It had been years since I had had the pleasure of throwing laden paper bags from the dirt road above over the heaps of garbage below to see how far down they would sail, but I resisted that impulse this one last run to the dump, instead placing the bags full of my father’s work clothes neatly at the top for scavengers to find—the Sioux, or the large families for whom the small-town dump was an open-air Goodwill Store.

It was ten years after my father’s death before my mother ever returned again to South Dakota. By then, that house, rented out for years, had blown away in a tornado. Only the basement, bulldozed over and filled with dirt, contained the leftovers of our lives: the dolls, books, school papers and trophies. I’d left those private things stacked away on shelves—things too valuable to throw away, yet not valuable enough to carry away to our new lives. I’ve been told that people from the town scavenged there, my friend from high school taking my books for her own children, my mother’s friend destroying the private papers. My brother-in-law had taken the safe away years before.

But last year, when I went to clear out my oldest sister’s attic in Minnesota, I found the dolls I thought had been buried long ago–their hair tangled and their dresses torn—as though they had been played with by generations of little girls. Not the neat perfection of how we’d kept them ourselves, lined up on the headboard bookcases of our beds —but hair braided, cheeks streaked with rouge, eyes loose in their sockets, dresses mismatched and torn. Cisette’s bride dress stetched to fit over Jan’s curves. My sister’s doll’s bridesmaid dress on my doll.

It felt a blasphemy to me. First, that my oldest sister would take her younger sisters’ dolls without telling us. Her own dolls neatly preserved on shelves in her attic guest bedroom, ours had been jammed into boxes with their legs sticking out the top. And in her garbage can were the metal sides of my childhood dollhouse, imprinted with curtains and rugs and windows, pried apart like a perfect symbol of my childhood.

Being cast aside as leftovers twice is enough for even inanimate objects. Saved from my sister’s garbage and cut in half, the walls of my childhood fit exactly into an extra suitcase borrowed from a friend for the long trip back to Mexico, where I now live. I’ll figure out a new life for them as room décor or the backgrounds of colossal collages that will include the dolls I’m also taking back with me.

Mexico is the place where lots of us have come to reclaim ourselves and live again. So it is with objects, too. Leftovers and hand-me-downs have a value beyond their price tags. It is all those lives and memories that have soaked up into them. In a way, we are all hand-me-downs. It’s up to us to decide our value, depending upon the meaning that we choose to impart both to our new lives and these old objects. Leftovers make the most delicious meals, sometimes, and in Mexico, we know just how to spice them up.

The prompt: Hand-Me-Downs—Clothes and toys, recipes and jokes, advice and prejudice: we all have to handle all sorts of hand-me-downs every day. Tell us about some of the meaningful hand-me-downs in your life.

Interlude

Disclaimer Notice: This is a work of fiction, not of fact!!!!

I have been dieting for months and I’m in fine fettle. I can see the admiring looks of several men as I enter the restaurant, along with the slightly irritated stares of their wives or girlfriends. I’m fresh from the beauty parlor: newly coiffed, manicured and pedicured, wearing a size smaller than I wore a month ago and several sizes smaller than a year ago. Feeling buff, I slide into a booth, fanning both hands over the smooth surface of the Formica table top, admiring my French manicure.

He enters the restaurant shortly after I do. Taking the long way around the aisle that runs between the tables in the center and the booths along the four sides, he scans the faces of diners with a curiosity that signals an interest in life. He is tall and intelligent-looking with a quirky doorknocker beard and mustache and a Hawaiian shirt—all elements of his appearance that call out for notice. I do not disappoint.

I watch him as he draws nearer, but drop my eyes as he approaches my booth. So it is that I am surprised when he stops in front of me and says, “May I ask you what you name is?”

I bring my eyes up to meet his. Is this the Cinderella story I’ve been waiting for my whole life? Quickly, my mind fills in the prior details. He noticed me on the road and followed me here. Or, he was driving by when he saw me enter the restaurant and, on a whim, seized the day and came in search of me. Or, this is an old and long-forgotten flame, someone from my past—a college or high school friend I haven’t seen for twenty years.

Without asking why or giving a smart answer, for once I merely answer the question. “Judy. Judy Dykstra-Brown,” I purr in a humorous, slightly sexy voice, not once looking away from his clear hazel eyes.

He does not disappoint. “I’ve been looking for you,” he says.

“I’ve been looking for you, too—for a very long time,” I answer in my best low flirtatious tone.

He reaches out toward me, and I extend my hand toward him as well; but in place of his own hand, he places something soft and warm in my palm.

“You must have dropped your wallet in the foyer,” he says to me, “You’re lucky that the right person found it.” He turns then and walks across the room to sit down at a table with a lovely woman in a white sundress and two darling tanned children. They are like a commercial for a Hawaiian vacation.

I open the wallet to see that all the money is intact, the driver’s license just slightly askew from where he must have withdrawn it to see the picture of its owner, and my mind replays his final words to me. “You’re lucky.”

“Welcome to Perkins!” The waitress interrupts my thoughts in a perky voice, living up to the name of her place of employment. I take the menu she proffers and order humble pie.

The Prompt: Greetings, Stranger—You’re sitting at a café when a stranger approaches you. This person asks what your name is, and, for some reason, you reply. The stranger nods, “I’ve been looking for you.” What happens next?

Crunchy, Soft and Piquant

The Prompt: Is there an unorthodox food pairing you really enjoy? Share with us the weirdest combo you’re willing to admit that you like — and how you discovered it.

Potato chips, ketchup and cottage cheese! I imagine this pairing came about by accident one day at a school or church picnic on a too-small plate, and some flavor memory insists there were baked beans and a hamburger on the same plate; but somehow the vital ingredients came to be the salty-crunchy chips, the creamy-soft cheese and the piquant perfection of Hunts Ketchup. (For the uninitiated, the process is to dip the chip in the ketchup and then scoop up the cheese.)

I don’t usually keep potato chips in the house anymore because I can’t be trusted with them, and cottage cheese is so expensive in Mexico that I don’t usually buy it; but when I make a trip to Costco in Guadalajara, invariably I’ll come home with one of their huge containers of cottage cheese and somehow, magically, potato chips appear (If you buy it, they will come) and the house echoes with the strains of some culinary Indian Love Call coming from the heart of my fridge, “When I’m calling you u u u u u u.” And so it is that the unlikely trio are reunited once again, probably late at night when even the dogs are fast asleep and no one is looking.

Justification

I spent all day in town today for business and for pleasure,

so by the time I got back home, I felt I’d had full measure

of driving-selling-trying on, shopping-eating-walking;

so I just thought I’d have some time that didn’t include talking.

I put my suit on thinking I would jump right in the pool,

but then the cat began to whine, the dogs commenced to drool—

sure signals it was feeding time—in this they were united.

They’ve learned their human serves their supper faster when invited.

The problem was, the dog food was still up in the car,

so I ran out to get it. (It wasn’t very far.)

I fed the dogs and cat, then found new flea collars I’d bought,

and so, of course, I had to put new collars on the lot.

Then, finally, the pool was mine—aerobic exercise

kept my body busy while a movie wooed my eyes

to disregard the time that passed while bending, kicking, flopping,

for when I am distracted, I am less intent on stopping.

With no prompt to finish early, I just went on and on.

Two hours passed so quickly that the setting of the sun

(and the ending of the movie—I guess I must admit)

finally gave the signal that it was time to quit.

But as I climbed the ladder, something poked my breast—

something sharp and lumpy that had made a little nest

there between my cleavage all my hours in the pool;

and when I drew it out you can’t image what a fool

I felt like, for this faux pas cannot help but win the prize

of all the times that I’ve done stupid things in any guise.

As teacher, daughter, writer, artist, sister, lover, friend,

I’ve committed stupid acts impossible to mend.

But this one takes the cake, I’m sure, as stupidest by far.

I’ve told you how I went to get the pet food from the car,

then fed and put flea collars on protesting dogs and cat.

(I doubt you’d do much better when dealing with all that!)

When I went out to do all this, I didn’t want to lose ‘em.

That’s why my car keys (with remote) wound up within my bosom!

Try as we may, those little indicators of age will sneak up on us. There is no plastic surgery for a sagging memory!!! (The Prompt today was: “Age is just a number,” says the well-worn adage. But is it a number you care about, or one you tend (or try) to ignore?”)

Wonder of wonders, when I put the key in the ignition the next morning, it worked!!! Saved on this one!